Shell-laminated structures: biomimicry from mollusk patterns

Shell-Laminated Structures: Biomimicry from Mollusk Patterns

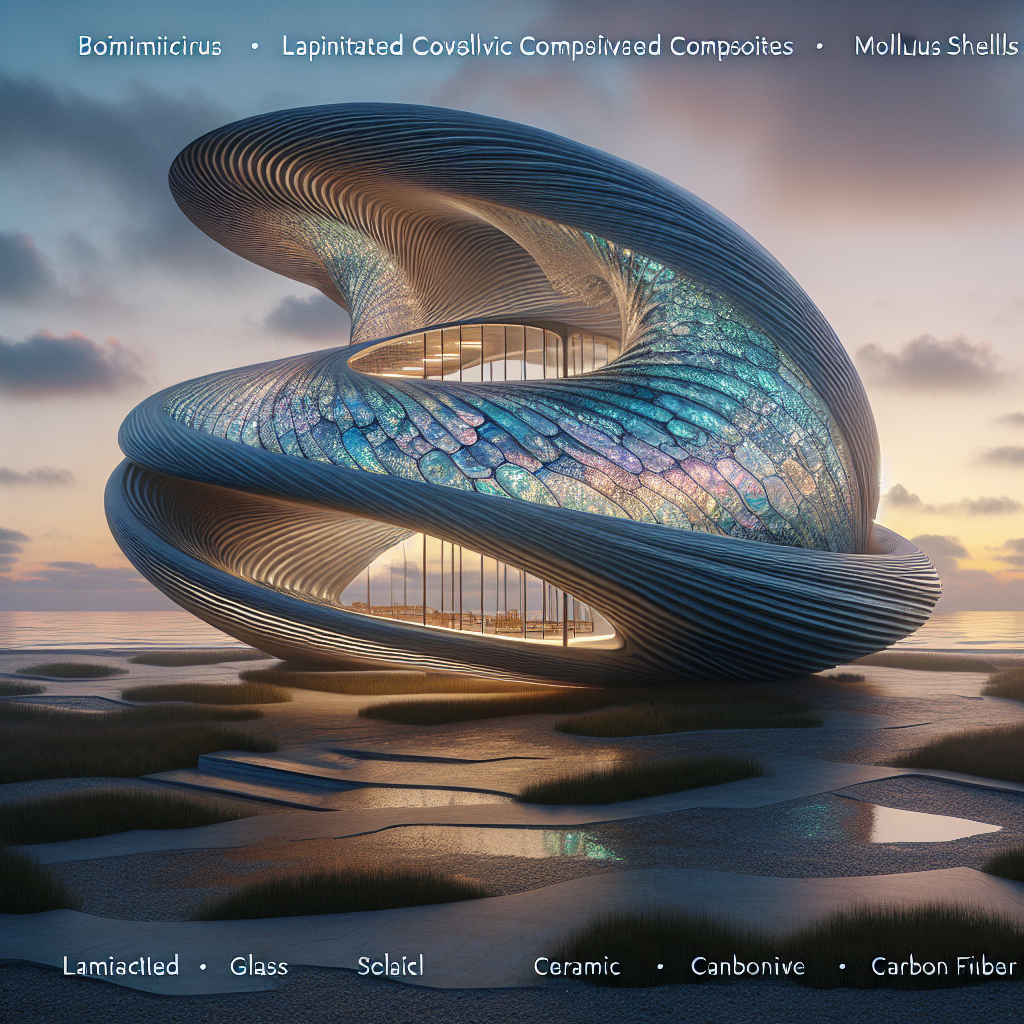

In the evolving landscape of architectural innovation, few concepts capture the imagination quite like shell-laminated structures. Drawing inspiration from the intricate microstructures of mollusk shells, this emerging design philosophy fuses biomimicry, material science, and parametric design to create forms that are simultaneously lightweight, resilient, and visually poetic. For architects and designers seeking the next frontier of sustainable, high-performance construction, the mollusk’s shell—an evolutionary masterpiece—offers a compelling blueprint.

The Science Behind Shell-Laminated Structures

Mollusk shells, particularly those of nacre-producing species, are natural composites that achieve extraordinary strength through layered architecture. Known scientifically as nacre or “mother of pearl,” these shells are composed of microscopic aragonite platelets bound by biopolymers, forming a hierarchical laminate that resists fracture and disperses stress efficiently. Translating this principle into architecture, shell-laminated structures emulate these biological strategies through layered composites of concrete, glass fiber, carbon fiber, or even bio-based resins.

This approach represents a paradigm shift from monolithic construction toward layered resilience. Instead of relying on bulk for strength, architects are now exploring how micro-scale layering can yield macro-scale performance. The result is a new generation of façades, roofs, and pavilions that are both structurally optimized and aesthetically evocative—mirroring the iridescent gradients and curvature of seashells.

From Ocean to Architecture: Biomimicry in Practice

The application of mollusk-inspired lamination extends beyond structural efficiency; it also redefines the relationship between form and function. The shell’s geometry—spiraling, tessellated, and subtly asymmetrical—has inspired computational models that generate self-supporting surfaces with minimal material waste. This echoes the ethos of biomimicry in design, where natural evolution becomes a teacher for sustainable innovation.

In practice, shell-laminated structures are being explored through parametric modeling and digital fabrication. Using algorithmic tools, designers can simulate the stress distribution patterns found in mollusk shells, then translate them into architectural skins that respond dynamically to environmental forces. The result is a fusion of organic logic and technological precision—an architecture that feels alive.

Material Innovation: Layering for Strength and Sustainability

The material science behind shell-laminated architecture is as fascinating as its biological muse. Researchers at ETH Zurich and MIT have studied nacre’s “brick-and-mortar” configuration to develop composite panels that mimic its toughness. These panels combine thin layers of glass or ceramic with flexible polymer interlayers, creating façades that can flex under stress rather than crack. Such materials are particularly relevant in the context of resilient building design, where adaptability and fracture resistance are paramount.

Moreover, the sustainable potential of these materials is significant. Bio-based laminates derived from chitin—the same biopolymer found in mollusk shells—are being developed as renewable alternatives to petroleum-based composites. This aligns with the broader movement toward biodegradable architecture, where material life cycles are designed to harmonize with ecological systems.

Architectural Aesthetics: The Poetics of Iridescence

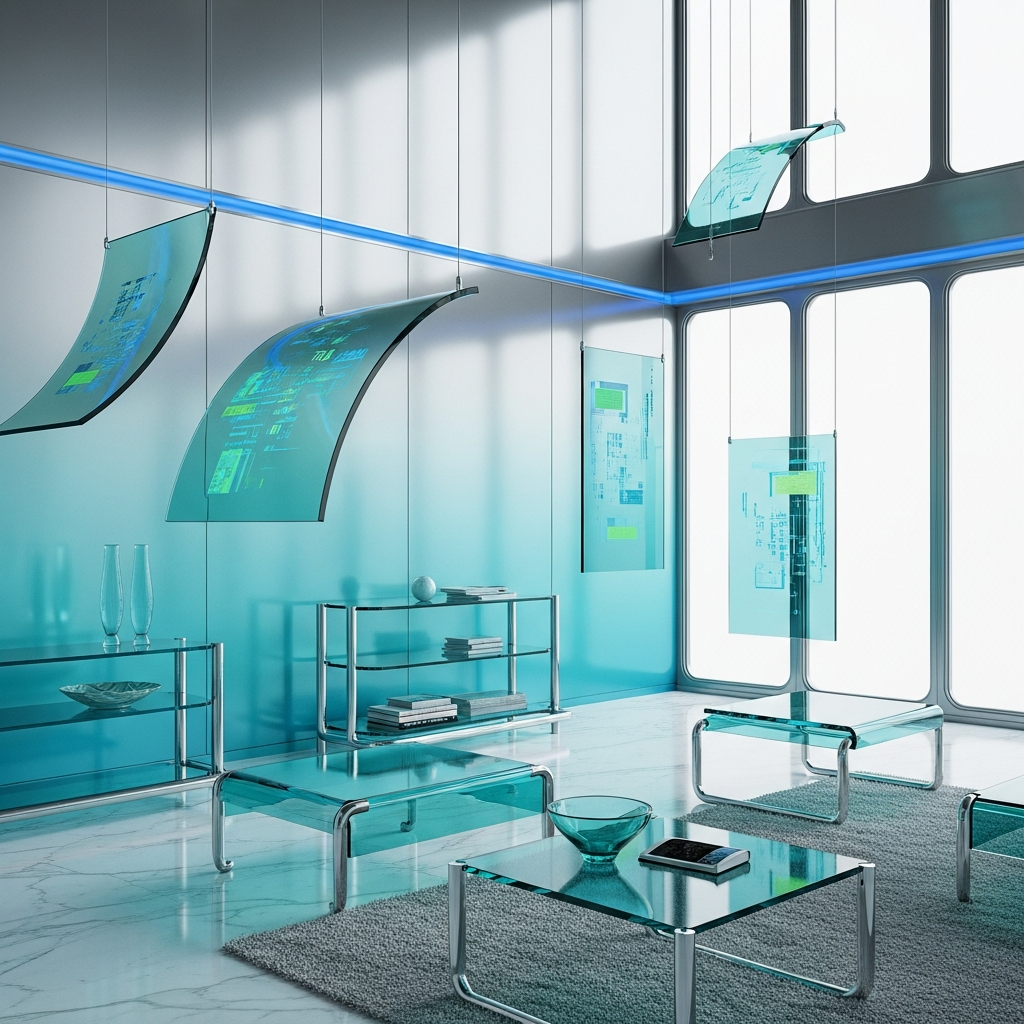

Beyond engineering, shell-laminated structures introduce a new visual language to contemporary architecture. Their layered composition interacts with light in mesmerizing ways, producing gradients of color and shadow reminiscent of underwater iridescence. When applied to façades or interior surfaces, these materials evoke a tactile sensuality that contrasts with the sterility of glass and steel modernism.

Imagine a civic pavilion whose curved roof shimmers like an abalone shell at dusk, or a museum façade that refracts daylight into subtle pearlescent hues. These are not mere aesthetic gestures—they are sensory experiences rooted in material intelligence. Such design thinking resonates with the principles of biophilic design, which emphasizes emotional and physiological connections between humans and nature.

Case Studies: From Research to Realization

Several pioneering projects have begun to translate mollusk-inspired lamination into built form. At the University of Stuttgart’s Institute for Computational Design and Construction (ICD), researchers developed a pavilion composed of thin, fiber-reinforced polymer shells arranged in layered patterns that mimic nacre’s microstructure. The result was a self-supporting, lightweight enclosure capable of spanning large distances with minimal material use.

Similarly, the “Seashell Pavilion” in Busan, South Korea, integrates laminated glass panels with embedded photonic films that replicate the optical behavior of nacre. As sunlight moves across its surface, the pavilion appears to breathe with shifting iridescence—a living sculpture of light and structure. These projects exemplify how biomimetic architecture can transcend imitation to achieve innovation.

Digital Fabrication and Computational Design

The precision required to emulate mollusk microstructures would be impossible without the advent of digital fabrication. Techniques such as CNC milling, robotic lamination, and 3D printing allow architects to construct layered geometries with millimetric accuracy. Computational design tools, meanwhile, simulate how these layers interact under load, enabling performance-driven optimization.

This digital-analog synergy is transforming how we conceive and build. By merging natural intelligence with algorithmic control, designers can craft structures that are both materially efficient and visually transcendent. It’s a continuation of the lineage that began with Gothic rib vaults and evolved through modernist shell structures—now reborn through the lens of biology and computation.

Environmental and Urban Implications

In an era defined by climate urgency, the lessons of mollusk shells extend beyond aesthetics. Their capacity to self-repair, distribute stress, and grow incrementally offers metaphors for adaptive urbanism. Cities could one day feature façades that respond to environmental stressors, adjusting their lamination density to optimize insulation or ventilation. Such ideas align with the vision of net-zero architecture, where performance and ecology are inseparable.

Moreover, shell-laminated systems could redefine how we approach retrofitting. Thin, lightweight composite panels can be layered over existing structures, enhancing strength and energy efficiency without the need for demolition. This layered approach to sustainability—adding rather than replacing—echoes the mollusk’s own evolutionary strategy of incremental adaptation.

The Future of Biomimetic Construction

As material science converges with digital design, shell-laminated architecture is poised to become a defining motif of 21st-century construction. It embodies a shift from brute-force engineering to intelligent materiality—from static forms to responsive skins. Architects are no longer merely designing enclosures; they are orchestrating living systems of matter and light.

The mollusk’s shell, once a humble artifact of marine life, now serves as a manifesto for architectural evolution. Its layered logic challenges us to rethink strength, beauty, and sustainability not as separate goals but as interdependent layers of the same structure. In doing so, it invites a new architectural language—one that is as resilient as it is radiant, as scientific as it is poetic.

In the words of contemporary design theorists, the future of architecture may not be built in concrete or steel, but in the laminated intelligence of nature itself. Shell-laminated structures are not just a technical innovation; they are a philosophical one—reminding us that the most advanced designs often begin in the ocean’s quiet depths.

Published on 12/15/2025