Rewilding orchard design: cities adopting fruit trees as public art

Rewilding Orchard Design: Cities Adopting Fruit Trees as Public Art

In the evolving narrative of urban design, a quiet yet radical movement is taking root—literally. Across the world, architects, landscape designers, and city planners are embracing rewilding orchard design as a new paradigm for public space. These are not the manicured, ornamental parks of the 20th century, but living, edible installations that merge ecological restoration with public art. Cities from Paris to Portland are planting fruit-bearing trees along boulevards, plazas, and rooftops, transforming civic environments into multisensory experiences where design, biodiversity, and community nourishment intersect.

The Rise of the Urban Orchard as Public Art

The concept of rewilding—once confined to rural conservation—has migrated into the heart of cities. According to the rewilding movement, the goal is to restore natural processes and native species to degraded ecosystems. When translated into urban design, this philosophy takes on a poetic form: fruit trees as living sculptures, evolving through the seasons, offering shade, scent, and sustenance.

In Paris, the Vergers Urbains initiative has turned neglected corners into micro-orchards, where apple, pear, and cherry trees coexist with public seating and sculptural installations. The visual rhythm of these trees—twisting trunks, flowering canopies, and fruit-laden branches—introduces a dynamic layer of biophilic design that redefines the aesthetics of civic beauty. As explored in biophilic design and its impact on human health and well-being, the integration of living systems into architecture not only enhances visual appeal but also improves psychological and physiological wellness.

From Utility to Symbolism: The Aesthetics of Edibility

The 21st-century city is increasingly expected to be both productive and beautiful. Rewilding orchard design bridges this dual expectation by transforming the act of cultivation into an art form. Fruit trees—once relegated to rural landscapes—are now being curated as sculptural elements within plazas, courtyards, and façades. Their cyclical nature—bloom, fruit, decay, renewal—mirrors the temporality of contemporary public art.

In London’s King’s Cross, the “Edible Bus Stop” project integrates fruit trees and herbs into transport corridors, turning waiting areas into fragrant, edible installations. The design language here is one of participatory aesthetics: the public becomes both viewer and caretaker. The polished steel planters reflect the sky and surrounding architecture, while the rough textures of bark and soil introduce tactile contrast—a dialogue between the urban and the organic.

This shift echoes the broader movement toward public art as a tool for social and environmental transformation. Where once monumental sculptures dominated civic spaces, today’s “living monuments” grow, adapt, and feed. The orchard becomes a metaphor for shared stewardship—a collective artwork authored by time, weather, and community.

Architectural Integration: Designing with Growth in Mind

Architects are now designing buildings and landscapes that anticipate growth, decay, and regeneration. In Tokyo, Kengo Kuma’s “Fruit Garden Plaza” integrates citrus trees into a lattice of bamboo and glass, creating a fragrant canopy that filters sunlight through translucent leaves. The result is a spatial choreography of scent and shadow—an ephemeral architecture that changes hourly with the sun’s trajectory.

Similarly, in Copenhagen, the firm SLA has reimagined public squares as urban orchards that double as climate-resilient infrastructure. The trees are strategically placed to absorb stormwater, reduce heat islands, and support pollinators. These designs exemplify what the green roof and rooftop garden movement has long championed: the fusion of ecological performance with aesthetic delight.

In this context, fruit trees are not decorative afterthoughts but structural protagonists. Their placement dictates circulation patterns, their root systems inform drainage design, and their seasonal changes influence the perception of time within the city. The orchard becomes a living blueprint—a slow architecture that resists the static perfection of traditional landscaping.

Community, Culture, and the Politics of Sharing

Beyond their ecological and aesthetic value, urban orchards embody a subtle political statement. They challenge the privatization of food systems and reassert the commons as a space of nourishment. In Berlin, the “Essbare Stadt” (Edible City) initiative encourages citizens to harvest fruit from public trees, fostering a culture of collective care. The act of picking an apple from a public branch becomes a small but profound gesture of participation in urban life.

Sociologists have noted that such initiatives contribute to what urban ecology scholars call “ecological citizenship”—a form of civic identity rooted in environmental awareness and mutual responsibility. The orchard, in this sense, becomes a social condenser, not unlike the communal courtyards of early modernist housing projects, but reimagined through the lens of sustainability and inclusivity.

The aesthetic of rewilding also resonates with contemporary design’s fascination with imperfection and natural processes. The moss creeping along a stone bench, the fallen fruit staining the pavement—these are not flaws but integral components of a living artwork. They recall the wabi-sabi aesthetic, where transience and decay are celebrated as expressions of authenticity.

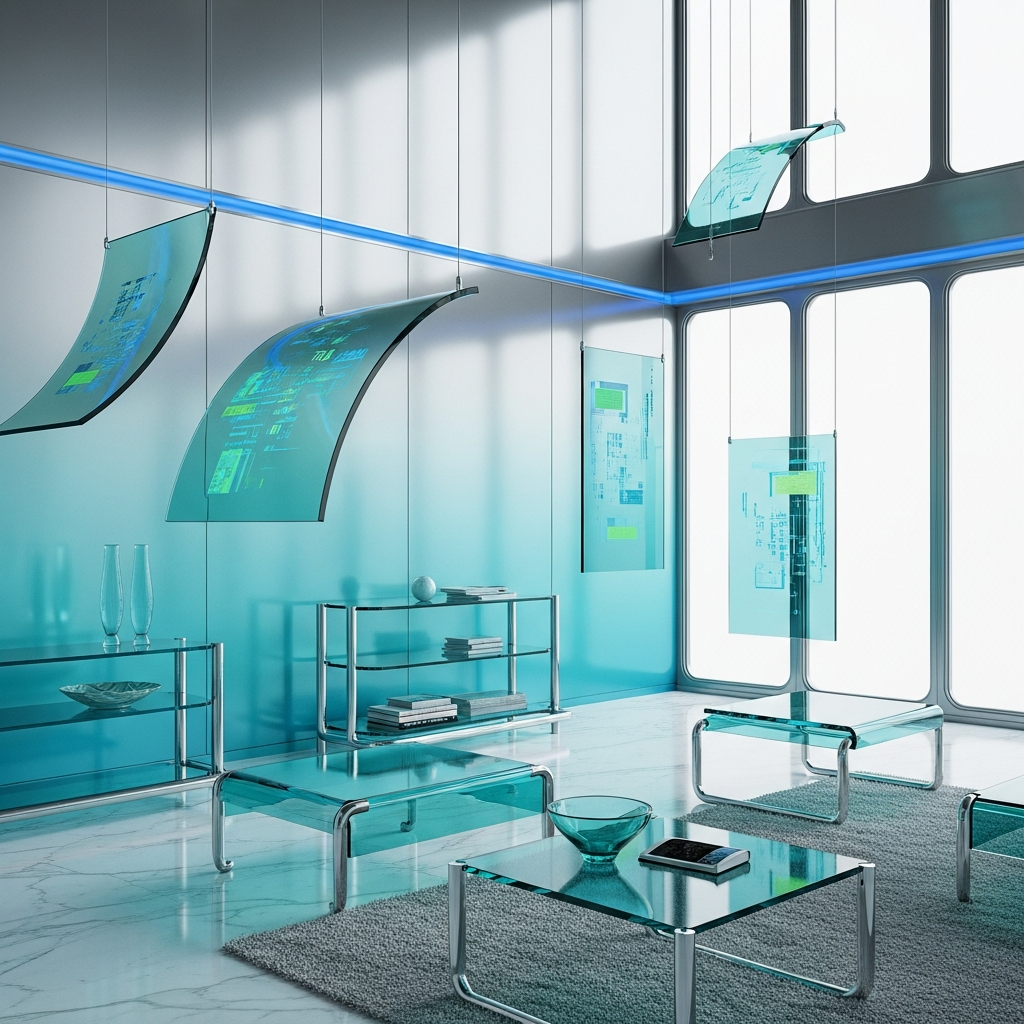

Data-Driven Design Meets Nature’s Chaos

While rewilding orchards may appear spontaneous, their success often depends on precise data modeling. Landscape architects now use GIS mapping, soil sensors, and microclimate simulations to determine optimal tree placement and species diversity. This fusion of technology and ecology echoes the design logic explored in AI in architecture, where algorithmic intelligence informs organic growth patterns.

In Milan, the “Bosco Fruttifero” project employs predictive analytics to monitor fruit yield, pollination cycles, and carbon sequestration. The data is visualized through interactive installations, allowing citizens to witness the orchard’s metabolic life in real time. Here, digital transparency enhances ecological literacy, turning the orchard into both a sensory and informational artwork.

Materiality and the Poetics of Maintenance

Designing for rewilding requires a reconsideration of materials and maintenance. The hardscape must accommodate root expansion, fallen fruit, and seasonal moisture. Architects are experimenting with permeable pavements, recycled stone aggregates, and modular planters that allow for root aeration. Benches are designed with integrated composting systems; rainwater channels double as irrigation.

Visually, these environments blur the boundary between built and grown. A polished concrete bench might cradle a wild fig tree; a corten steel trellis might host climbing vines heavy with grapes. The interplay of patina, fruit, and foliage creates a sensory richness that challenges the sterile minimalism of conventional urban design. It’s a return to tactility, to scent, to the unpredictable choreography of nature.

The Future of Rewilded Cities

As climate pressures intensify, cities are rethinking what constitutes infrastructure. The orchard, once a symbol of rural abundance, is emerging as a model for urban resilience. It cools, feeds, shelters, and inspires. In doing so, it redefines the relationship between art, architecture, and ecology.

Rewilding orchard design is not merely a trend—it’s a philosophical shift. It invites architects to design with humility, acknowledging that the most profound forms of beauty may come not from control, but from coexistence. The city of the future may not be a forest of glass towers, but a mosaic of fruiting canopies—each tree a living artwork, each harvest a shared celebration of design’s most elemental purpose: to sustain life.

In this sense, the rewilded orchard stands as both a spatial and ethical manifesto. It reminds us that public art need not be static, and that architecture’s highest calling may be to nurture—not dominate—the natural world.

By integrating fruit trees into the urban fabric, cities are not just greening their streets—they are reimagining what it means to design for abundance, connection, and renewal.

Keywords: rewilding orchard design, urban orchards, public art, biophilic design, sustainable cities, ecological architecture, fruit trees in urban design

Author: Editorial Team, Mainifesto Magazine