Multisensory Architecture: Designing with Sound, Light, Smell, and Touch

Multisensory Architecture: Designing with Sound, Light, Smell, and Touch

In the contemporary landscape of architecture and interior design, a profound shift is underway—one that transcends the purely visual. Multisensory architecture is redefining how we experience space, merging science, art, and psychology to engage all human senses. No longer satisfied with structures that simply look beautiful, architects and designers are crafting environments that sound, feel, and even smell harmonious. This approach transforms buildings into living, breathing experiences—immersive worlds that respond to our emotions, memories, and physical presence.

The Rise of Multisensory Thinking in Architecture

For decades, modern architecture was dominated by the visual. Clean lines, minimalist palettes, and sculptural forms defined the discipline. Yet, as neuroscience and environmental psychology advanced, it became clear that human perception of space is multisensory. Our brains process spatial experience through an intricate interplay of sound, light, temperature, texture, and scent. The result is a growing movement toward sensory design—a philosophy that prioritizes emotional resonance and physical well-being over mere aesthetics.

Architect Juhani Pallasmaa, in his seminal work The Eyes of the Skin, argued that architecture must engage the entire body, not just the eyes. Today, this principle is being reinterpreted through digital tools, responsive materials, and environmental data. From biophilic design that reconnects us with nature to acoustic engineering that enhances social interaction, multisensory architecture is reshaping how we inhabit the built world.

Sound: The Invisible Architecture

Sound is one of the most overlooked yet powerful spatial elements. The acoustics of a space can dictate mood, communication, and even productivity. In a cathedral, reverberation evokes awe; in a library, silence invites introspection. Today’s architects are rediscovering the art of acoustic design—not as an afterthought, but as a core architectural language.

Studios like Snøhetta and Arup have pioneered “sonic architecture,” integrating sound mapping and material analysis to shape environments that respond to human activity. The Oslo Opera House, for instance, uses wood and stone to diffuse sound naturally, creating a subtle acoustic gradient that enhances both performance and audience immersion. Similarly, projects such as the importance of acoustic comfort in interior design highlight how spatial soundscapes can improve mental well-being in homes and workplaces.

Emerging technologies are amplifying this trend. Responsive walls embedded with micro-speakers can adjust ambient sound levels in real time, while parametric modeling allows designers to sculpt acoustic forms that double as visual art. These innovations mark a new era where architecture doesn’t just contain sound—it composes it.

Light: The Architecture of Emotion

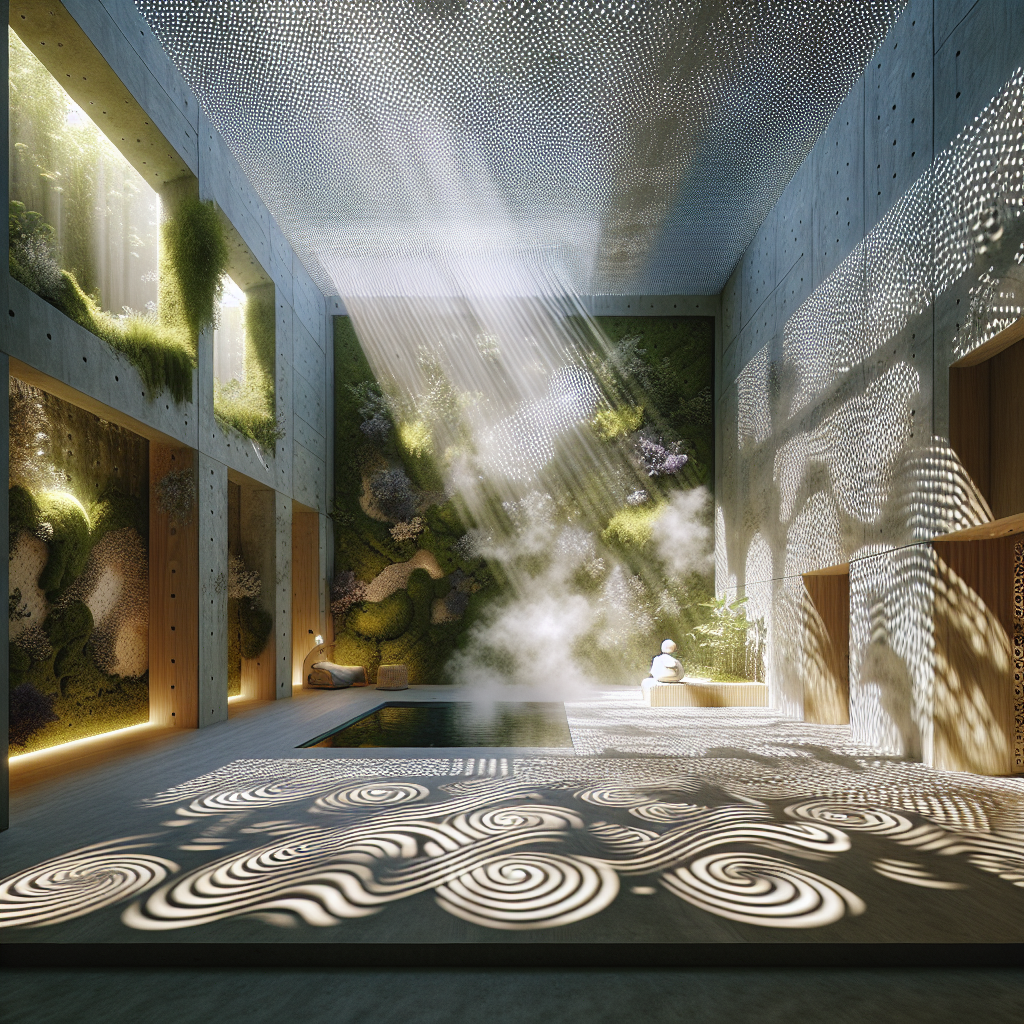

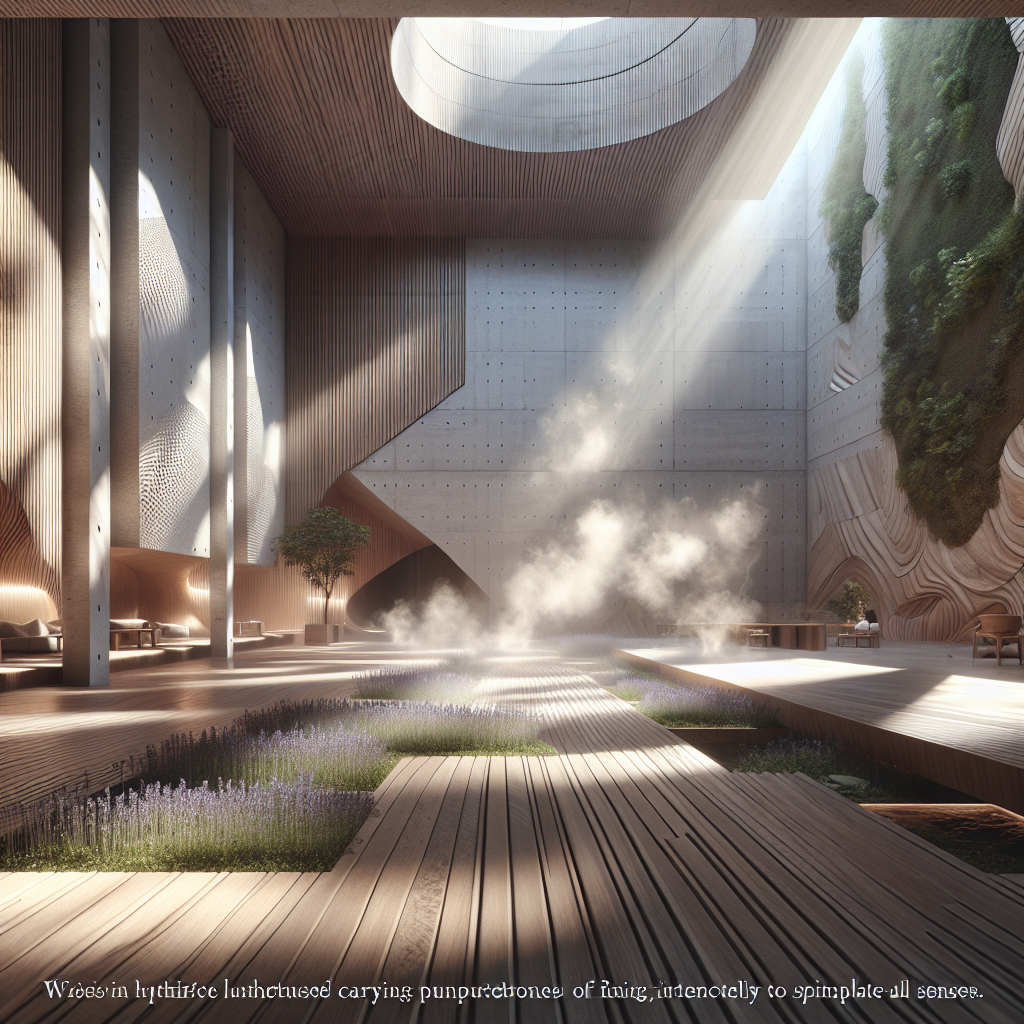

Light has always been the architect’s most expressive medium. Yet in multisensory design, it becomes more than illumination—it becomes emotional choreography. Natural light, filtered through perforated screens or clerestory windows, creates rhythms that shift with the day. Artificial lighting, meanwhile, is evolving into a dynamic tool for psychological modulation.

Studies by the International Association of Lighting Designers show that light intensity and color temperature directly influence mood and circadian rhythm. Architects are leveraging this knowledge to design adaptive lighting systems that mimic the natural progression of daylight. In wellness-focused environments—spas, hospitals, and co-working spaces—light is used to stimulate alertness or induce calm, aligning spatial experience with biological needs.

Designers like Olafur Eliasson have elevated light into a tactile phenomenon. His installations, often blending mist, mirrors, and chromatic filters, invite visitors to feel light as a physical presence. Similarly, the concept of bioluminescent lighting in architectural design explores organic illumination that glows softly, transforming interiors into living ecosystems of light.

Smell: The Forgotten Sense of Space

While vision and sound dominate architectural discourse, olfactory design is quietly emerging as a frontier of sensory innovation. Scent has a direct neurological link to memory and emotion, making it a potent tool for spatial storytelling. From the cedar aroma of a Japanese teahouse to the mineral scent of rain-soaked concrete, smell anchors us to place in ways no visual cue can replicate.

Some contemporary architects are integrating scent diffusers into HVAC systems or structural elements—a concept explored in fragrant architecture. In retail and hospitality, curated olfactory experiences are being used to reinforce brand identity and evoke emotional connection. A boutique hotel might infuse its lobby with notes of bergamot and leather, while a wellness center employs lavender and eucalyptus to signal relaxation.

Research from the University of Oxford’s Crossmodal Research Laboratory suggests that scent can even alter spatial perception—making rooms feel larger, warmer, or more intimate depending on the aromatic profile. As sustainability and wellness converge, natural essential oils and biodegradable scent carriers are replacing synthetic fragrances, aligning olfactory design with ecological ethics.

Touch: The Texture of Emotion

Touch grounds architecture in the body. The grain of wood beneath the fingertips, the coolness of marble, the roughness of exposed concrete—all evoke visceral responses that define our relationship with space. In an era dominated by digital interfaces, tactile design offers a necessary counterbalance, reintroducing material intimacy into our built environments.

Architects are increasingly exploring haptic materials that invite interaction. Soft textiles, textured ceramics, and responsive surfaces that change temperature or texture blur the boundary between user and structure. The resurgence of craftsmanship, as seen in projects like the art of craftsmanship in interior design, underscores a renewed appreciation for material authenticity.

Moreover, advances in haptic technology are transforming touch into a programmable experience. Smart materials embedded with sensors can react to human presence—warming under a hand’s pressure or vibrating gently to signal interaction. These innovations are particularly relevant in inclusive design, offering new ways to make architecture accessible to people with visual or sensory impairments.

Designing for the Whole Body

Multisensory architecture is not a trend—it’s a paradigm shift. It challenges the Cartesian separation of mind and body, proposing instead that architecture should be experienced holistically. This philosophy resonates with the growing emphasis on well-being, inclusivity, and sustainability in design. By engaging all senses, architects can create spaces that nurture rather than overwhelm, that communicate through atmosphere rather than ornament.

Projects like the Therme Group’s wellness resorts or Heatherwick Studio’s tactile urban interventions demonstrate how multisensory design can enhance both public and private life. These environments use soundscapes, lighting gradients, and material contrasts to foster emotional balance and social connection. In workplaces, multisensory strategies are being used to reduce stress and boost creativity, while in residential architecture, they cultivate intimacy and belonging.

The Future of Sensory Design

As climate, technology, and culture continue to evolve, the future of architecture lies in experiential intelligence—spaces that sense, adapt, and communicate. Artificial intelligence and biomimetic materials are enabling buildings to respond dynamically to human presence, adjusting acoustics, light, and scent in real time. This aligns with broader innovations in responsive design and smart architecture, where the built environment becomes an active participant in daily life.

Ultimately, multisensory architecture invites us to rethink what it means to inhabit space. It’s not about spectacle but synesthesia—the blending of sensory boundaries to create meaning. In a world increasingly mediated by screens, this return to embodied experience feels both radical and necessary. The future of design will not only be seen—it will be heard, touched, and felt in every breath.

Keywords: multisensory architecture, sensory design, acoustic architecture, olfactory design, tactile materials, lighting design, experiential architecture, responsive environments, emotional design, architectural innovation.