Transformable garments wearable: architecture doubling as personal shelters

Transformable Garments Wearable: Architecture Doubling as Personal Shelters

In an era defined by mobility, climate uncertainty, and technological hybridity, the boundaries between architecture and fashion are dissolving. The rise of transformable garments wearable—structures that act as both clothing and personal shelters—signals a profound shift in how we conceive of protection, privacy, and adaptability. These designs, often emerging from the intersection of architecture, material science, and performance design, reimagine the human body as a dynamic site of habitation. What was once a poetic metaphor—“wearing one’s home”—is now a tangible, engineered reality.

The Architecture of the Body

Architecture has long been about shelter, permanence, and stability. Fashion, by contrast, celebrates ephemerality, movement, and expression. Yet the convergence of these two disciplines has become increasingly visible in the last decade. From the inflatable cocoons of Lucy McRae to the modular exoskeletons of Iris van Herpen, designers are exploring how garments can serve as micro-architectures—responsive, protective, and deeply personal.

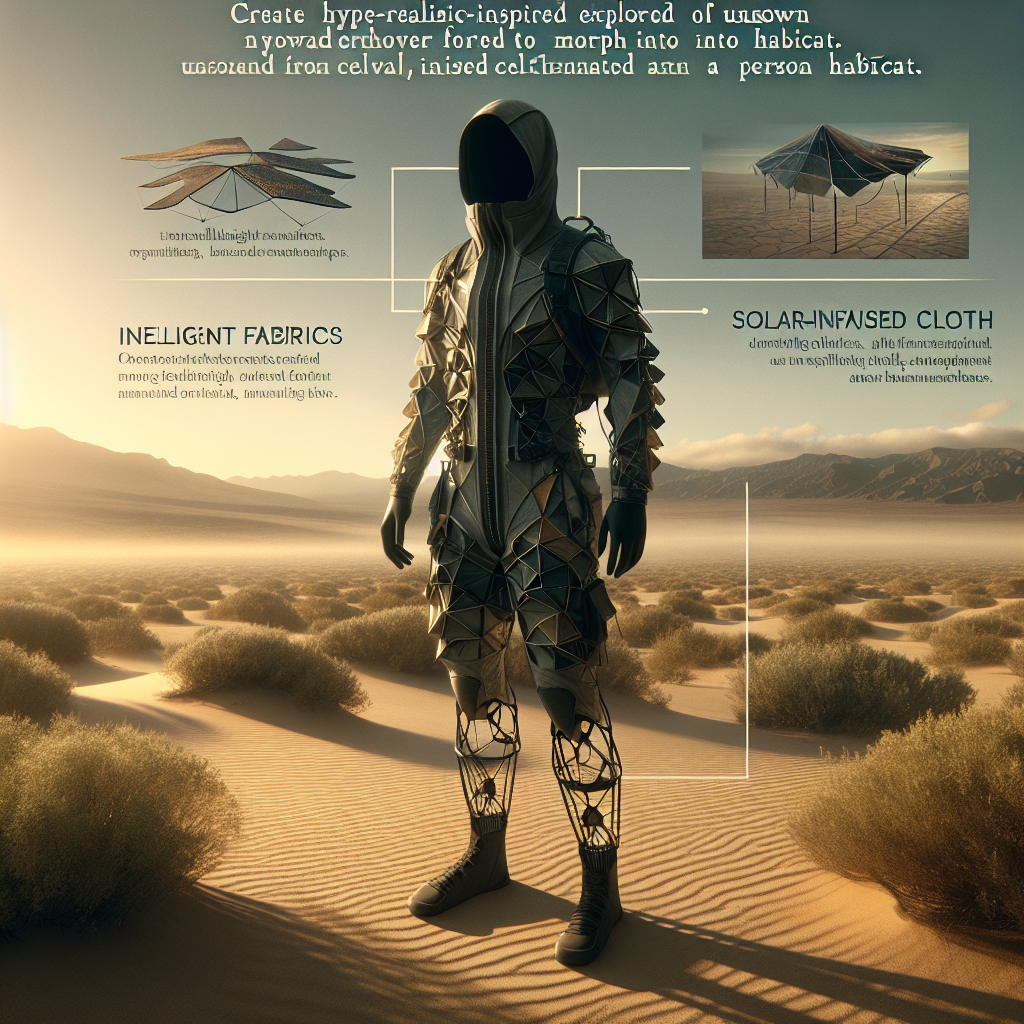

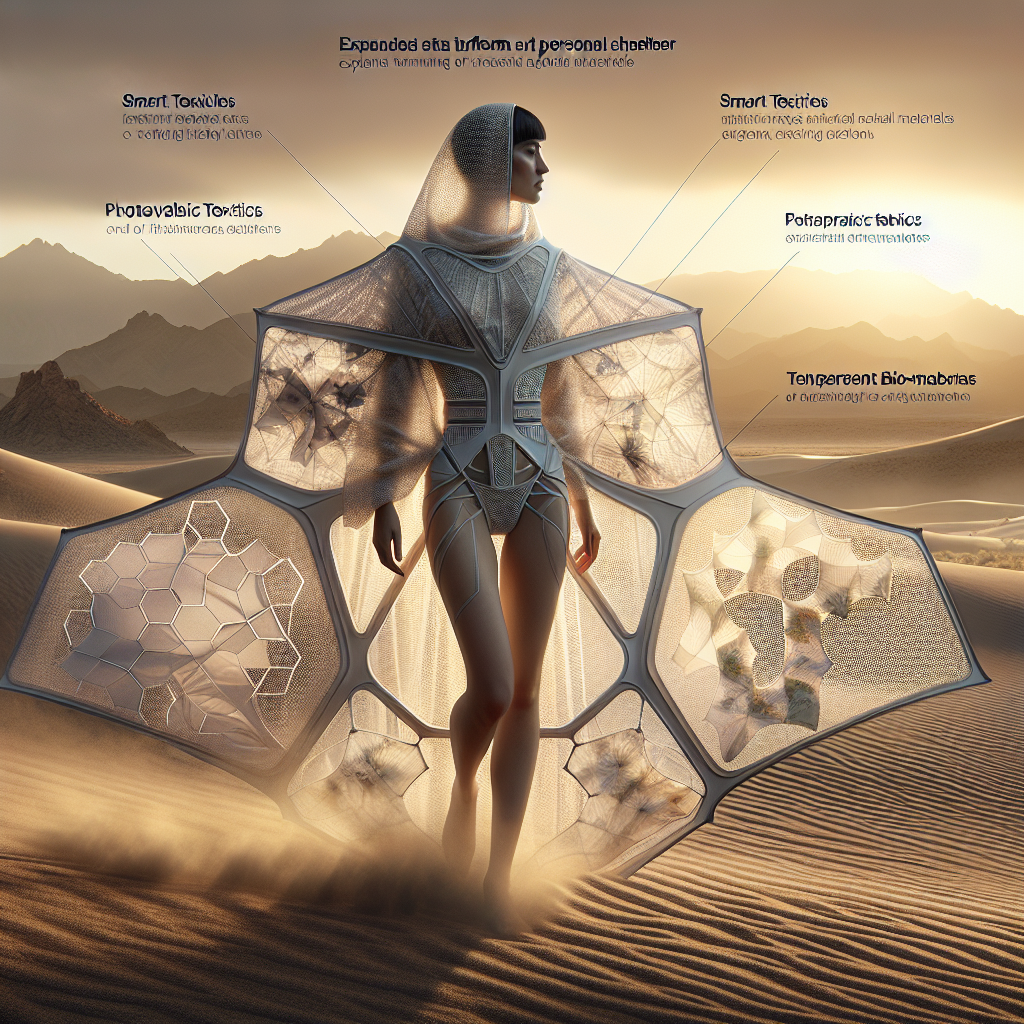

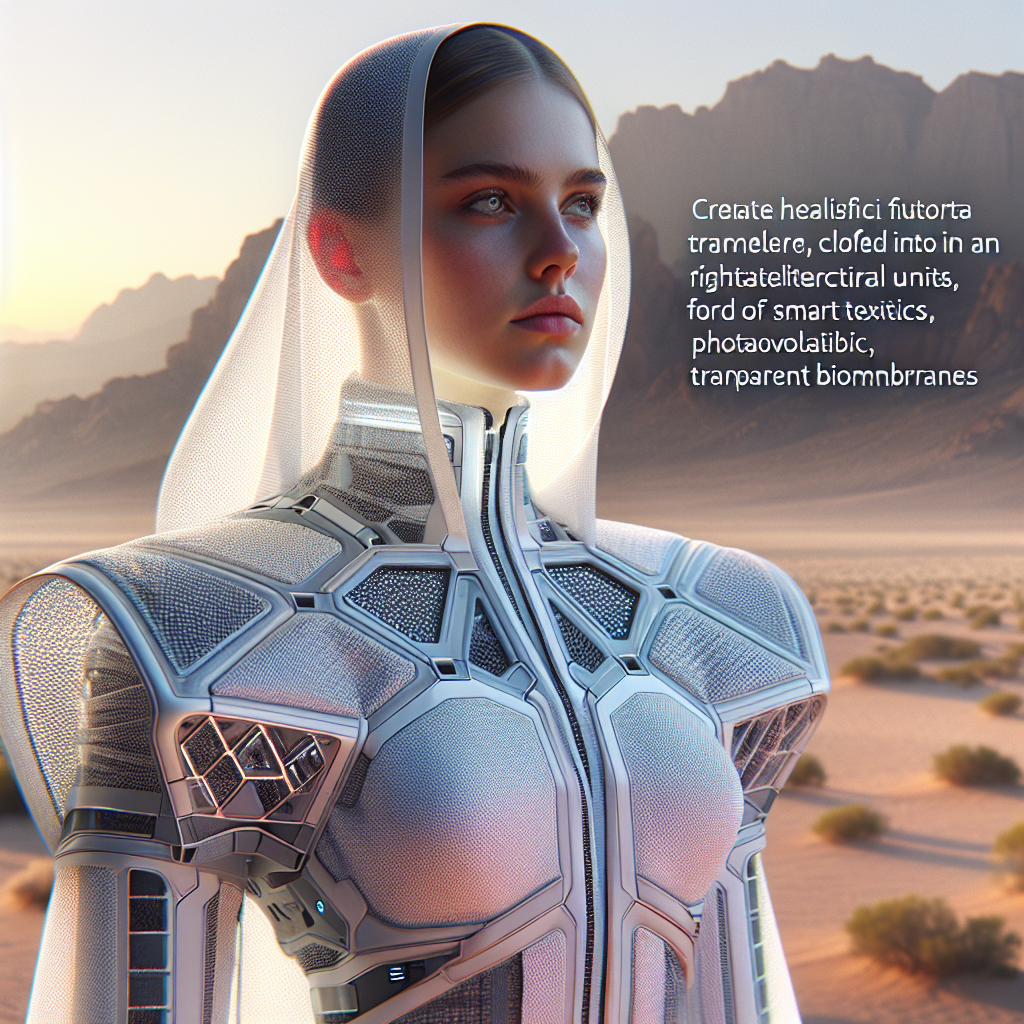

These wearable shelters embody the principles of adaptive architecture, translating spatial intelligence into portable, body-scaled environments. The materials—often lightweight composites, smart textiles, or bioengineered membranes—mirror the innovations seen in responsive building design. The result is a new typology: clothing that expands, contracts, or reconfigures itself in response to environmental stimuli such as temperature, humidity, or air quality.

From Nomadism to Necessity

The concept of wearable architecture is not merely an aesthetic experiment; it is increasingly a social and ecological necessity. As climate migration accelerates and urban density intensifies, the need for mobile, self-sufficient habitats grows. The design community’s response to climate displacement has already yielded innovative solutions in emergency housing and modular shelters. Transformable garments extend this logic to the individual scale, offering autonomy and resilience in unpredictable environments.

Designers like Jun Kamei, whose “Amphibio” garment allows underwater breathing through a 3D-printed gill membrane, or the interdisciplinary collective Urban Nomads, who craft foldable tents integrated into coats, exemplify this shift. Their work reflects a broader trend toward sustainable design—a movement that values adaptability and minimal environmental impact over static consumption.

Material Intelligence and Responsive Textiles

At the heart of this transformation lies material innovation. Smart fabrics embedded with sensors, phase-change materials, and photovoltaic fibers enable garments to react to environmental changes in real time. These textiles blur the line between skin and shelter, transforming the wearer into an active participant in their own environmental regulation.

Consider the recent experiments in biophilic design, where natural systems inspire architectural and product solutions. Similarly, wearable shelters increasingly draw from biological analogies—folding like leaves, breathing like lungs, or expanding like flowers. The aesthetic is not purely functional; it is poetic, merging the organic with the engineered in a choreography of survival and beauty.

Some prototypes integrate solar-powered panels woven into the fabric, enabling users to charge devices or power embedded heating systems. Others employ nanofibers that filter pollutants, turning the garment into a wearable air purifier. The fusion of sustainability and self-sufficiency defines this new design frontier.

Designing for the Mobile Citizen

In cities where space is scarce and lifestyles are increasingly nomadic, the idea of carrying one’s environment is deeply resonant. The micro-living movement has already redefined domestic architecture, prioritizing flexibility and compactness. Transformable garments extend these principles beyond the home, allowing the body itself to become the architecture.

Imagine a coat that unfolds into a sleeping pod, or a jacket that inflates into a temporary pavilion. These designs are not science fiction—they are being tested in design schools and research labs across Europe and Asia. The architectural language of these garments—folds, hinges, tensile membranes—echoes the vocabulary of deployable structures used in disaster relief or space exploration. The difference lies in scale and intimacy: these are architectures worn, not inhabited.

Case Studies: The Wearable Habitat

One of the most compelling examples is the “Habitat Wear” project by architect and designer Ying Gao. Her garments, made from photoluminescent textiles and kinetic actuators, respond to human proximity and light levels, creating a living, breathing façade around the body. The project challenges conventional distinctions between public and private space, proposing a wearable boundary that is both porous and protective.

Similarly, the “Wearable Shelter” by Australian designer Lucy Orta transforms into a tent, sleeping bag, or communal pod, addressing the humanitarian dimensions of design. Orta’s work bridges art and activism, using wearable architecture to question the politics of belonging and displacement. Her creations resonate with the ethos of socially responsible design, emphasizing empathy and inclusivity through form.

In a more speculative vein, the “Urban Armor” collection by MIT’s Tangible Media Group integrates responsive polymers that stiffen upon impact, offering both protection and structure. The garment becomes a kinetic exoskeleton—part clothing, part architecture, part prosthetic.

Ethics, Aesthetics, and the Future of Shelter

As wearable architecture evolves, it raises profound ethical and aesthetic questions. Who owns the data collected by sensor-embedded garments? How do we balance privacy with connectivity? And what happens when the line between the built environment and the human body dissolves entirely?

From an aesthetic standpoint, these designs redefine beauty as adaptability. The visual language of transformable garments—layered, modular, kinetic—reflects a world in flux. The elegance lies not in permanence but in transformation, echoing the principles of modular design and responsive architecture. As wearable shelters become more sophisticated, they may also become more invisible—integrated seamlessly into daily life, like a second skin.

Beyond Fashion: Toward a New Architectural Paradigm

The implications of this convergence extend far beyond fashion. For architects, the notion of wearable space challenges the very definition of building. It invites a rethinking of scale, permanence, and authorship. The architect becomes a choreographer of experiences rather than a constructor of static forms. The body becomes both the site and the subject of design.

In this context, wearable architecture aligns with broader movements in biodegradable architecture and circular design. Both seek to minimize waste, maximize adaptability, and create systems that evolve with their users. The ultimate goal is not to build more, but to build smarter—structures that grow, fold, and breathe in harmony with human life.

A Vision of Portable Futures

As the 21st century unfolds, the fusion of architecture and fashion may redefine what it means to inhabit the world. The transformable garment wearable is more than a design innovation—it is a philosophical statement about mobility, identity, and resilience. It suggests a future where architecture is not a place we enter, but something we carry with us; where the home is not a fixed address, but a living extension of the self.

In this vision, every fold, seam, and surface becomes a site of possibility. The shelter of tomorrow may not rise from the ground—it may unfurl from our shoulders.

Keywords: transformable garments wearable, wearable architecture, personal shelters, adaptive design, responsive textiles, sustainable fashion, mobile architecture