Syntropic gardens designing: landscapes that grow in mutually beneficial ways

Syntropic Garden Designing: Landscapes That Grow in Mutually Beneficial Ways

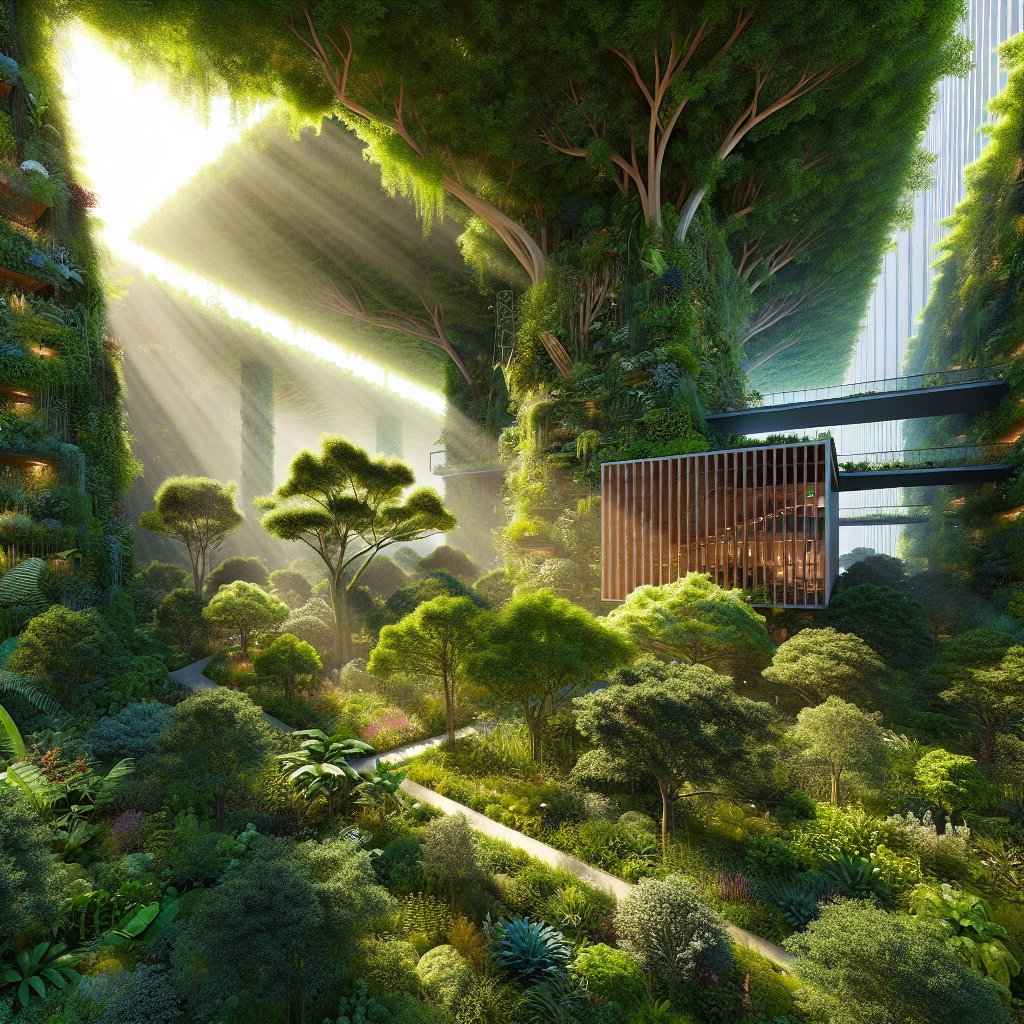

In the evolving dialogue between architecture and ecology, few concepts have captured the imagination of designers and environmentalists alike as powerfully as syntropic garden design. Rooted in the philosophy of regeneration rather than mere sustainability, syntropic systems transform landscapes into living, self-organizing ecosystems—spaces where every plant, microorganism, and human intervention contributes to a symphony of mutual benefit. For architects and landscape designers, this approach offers a blueprint for the future: a way to design not just for nature, but with it.

The Philosophy Behind Syntropy

The term “syntropy” was popularized by Swiss agroforester Ernst Götsch, whose pioneering work in Brazil redefined the relationship between agriculture and natural succession. Unlike conventional farming or ornamental landscaping, syntropic design mimics the ecological succession processes found in untouched forests. It replaces extraction with regeneration, monoculture with biodiversity, and control with collaboration.

In essence, syntropic gardens are designed to evolve. Each layer—trees, shrubs, herbs, groundcovers, and decomposers—plays a role in maintaining the system’s health. The result is a landscape that becomes more fertile, more complex, and more beautiful over time. For designers accustomed to static compositions, syntropy invites a radical shift: to think of landscapes as dynamic, living architectures that mature and transform with the seasons.

Designing for Mutual Growth

At the heart of syntropic garden design lies the principle of mutualism. Every element in the system supports another. Tall canopy trees provide shade and moisture retention for delicate understory plants; groundcovers prevent erosion and enrich the soil; decomposing leaves feed the microbial life that sustains root systems. This interconnectedness mirrors the structural logic of biophilic design—where built environments emulate natural processes to enhance human well-being.

For architects, the implications are profound. Imagine residential courtyards that double as edible micro-forests, or public plazas where layered vegetation naturally regulates temperature and air quality. The design vocabulary of syntropy is not ornamental—it’s performative. It turns gardens into productive ecosystems that yield food, biodiversity, and emotional nourishment.

From Soil to Structure: The Aesthetic of Regeneration

Visually, syntropic gardens defy the manicured symmetry of traditional landscaping. They are lush, textural, and deliberately irregular—an aesthetic of abundance rather than control. Layers of foliage overlap in a choreography of heights and hues: banana leaves arching over cassava shrubs, papaya trunks punctuating the skyline, and a carpet of legumes weaving nitrogen into the soil. The palette is not dictated by human preference but by ecological function.

In architectural terms, this organic complexity aligns with the current fascination for biomimicry and adaptive design. Just as a building might use responsive facades to regulate light and temperature, a syntropic garden self-adjusts to environmental changes. The visual result is a landscape that feels alive—its forms shifting subtly with each growth cycle, its textures deepening as organic matter accumulates.

Integrating Syntropy into Urban Design

Urban environments, often defined by impermeable surfaces and fragmented green spaces, stand to gain immensely from syntropic principles. By designing multi-layered urban gardens, architects can reintroduce ecological succession into city life. Rooftops, courtyards, and even vertical facades can become micro-ecosystems that restore biodiversity and improve microclimates.

In São Paulo, for instance, several design studios have begun experimenting with syntropic rooftops—terraced layers of edible and ornamental plants that not only sequester carbon but also provide fresh produce for residents. Similar projects are emerging in Lisbon and Melbourne, where designers are reimagining the urban garden as a living infrastructure rather than decorative afterthought.

This shift parallels the rise of green roof architecture and urban farming, yet syntropy pushes the concept further. It asks cities to become regenerative organisms—systems that give back more than they consume.

Architectural Collaboration with Nature

Integrating syntropic design into architecture requires a rethinking of materials, spatial organization, and maintenance cycles. Designers must plan for growth, decay, and renewal as integral parts of the built environment. This approach resonates with the principles of circular design, where waste is redefined as resource and longevity is measured in adaptability rather than permanence.

Consider a pavilion constructed from locally sourced timber, surrounded by a syntropic garden that provides both shade and structural cooling. Over time, as the vegetation matures, the pavilion’s microclimate evolves—reducing energy demands and enhancing comfort. The architecture becomes symbiotic, its success measured not by static beauty but by ecological performance.

Case Study: Fazenda da Toca, Brazil

One of the most compelling examples of syntropic design in practice is Fazenda da Toca in São Paulo state. Originally a degraded cattle ranch, it was transformed into a thriving agroforestry system under Götsch’s guidance. Rows of fruit trees, native species, and crops are interplanted in a way that mimics forest succession. The result is a landscape that regenerates itself—producing food while restoring soil health and biodiversity.

For architects visiting the site, the experience is revelatory. The spatial logic of the farm—its layered canopies, filtered light, and rhythmic planting patterns—feels architectural. It’s a reminder that design can orchestrate living systems with the same precision as it shapes concrete or glass.

Designing for Time: The Fourth Dimension

Traditional landscape architecture often freezes a moment in time—a garden at its most photogenic. Syntropic design, by contrast, embraces temporal beauty. It acknowledges that landscapes evolve, that decay is as vital as growth. This temporal awareness introduces a new dimension to design thinking: one that values change as an aesthetic and ecological asset.

For designers, this means crafting frameworks rather than final forms. Pathways may shift as vegetation expands; sightlines may blur as canopies mature. The designer’s role becomes that of a conductor, setting the initial rhythm and allowing nature to compose the symphony.

The Future of Syntropic Landscapes in Architecture

As climate resilience becomes a defining criterion in contemporary design, syntropic principles offer a pathway toward regenerative architecture. They align with global sustainability goals and respond to the urgent need for carbon sequestration, biodiversity restoration, and food security. More importantly, they propose a new aesthetic—one that celebrates cooperation over control, abundance over austerity.

In the coming years, we can expect to see syntropic thinking influencing not only gardens but also building envelopes, public spaces, and urban planning frameworks. Imagine façades that host layered vegetation designed for succession, or plazas that regenerate soil through seasonal planting cycles. The boundary between architecture and ecology is dissolving, giving rise to hybrid typologies that are as alive as they are designed.

A New Paradigm of Design Intelligence

Syntropic garden design challenges the notion of human dominance over nature. It invites architects and designers to act as facilitators of life processes rather than mere creators of form. This shift represents a profound evolution in design intelligence—one that values collaboration, resilience, and the quiet sophistication of systems that sustain themselves.

In this light, syntropy is not just a method of gardening; it’s a philosophy of coexistence. It’s the art of designing landscapes that teach us how to live in balance—spaces where architecture and ecology merge into a single, breathing organism.

As the boundaries between built and natural environments continue to blur, syntropic gardens stand as living testaments to what design can achieve when it embraces the wisdom of nature’s own architecture.

Keywords: syntropic garden design, regenerative landscapes, biophilic architecture, sustainable design, urban ecology, agroforestry, circular design, ecological succession, landscape architecture, climate resilience.