Retro bubble architecture: modern updates to 1960s inflatable pavilions

Retro Bubble Architecture: Modern Updates to 1960s Inflatable Pavilions

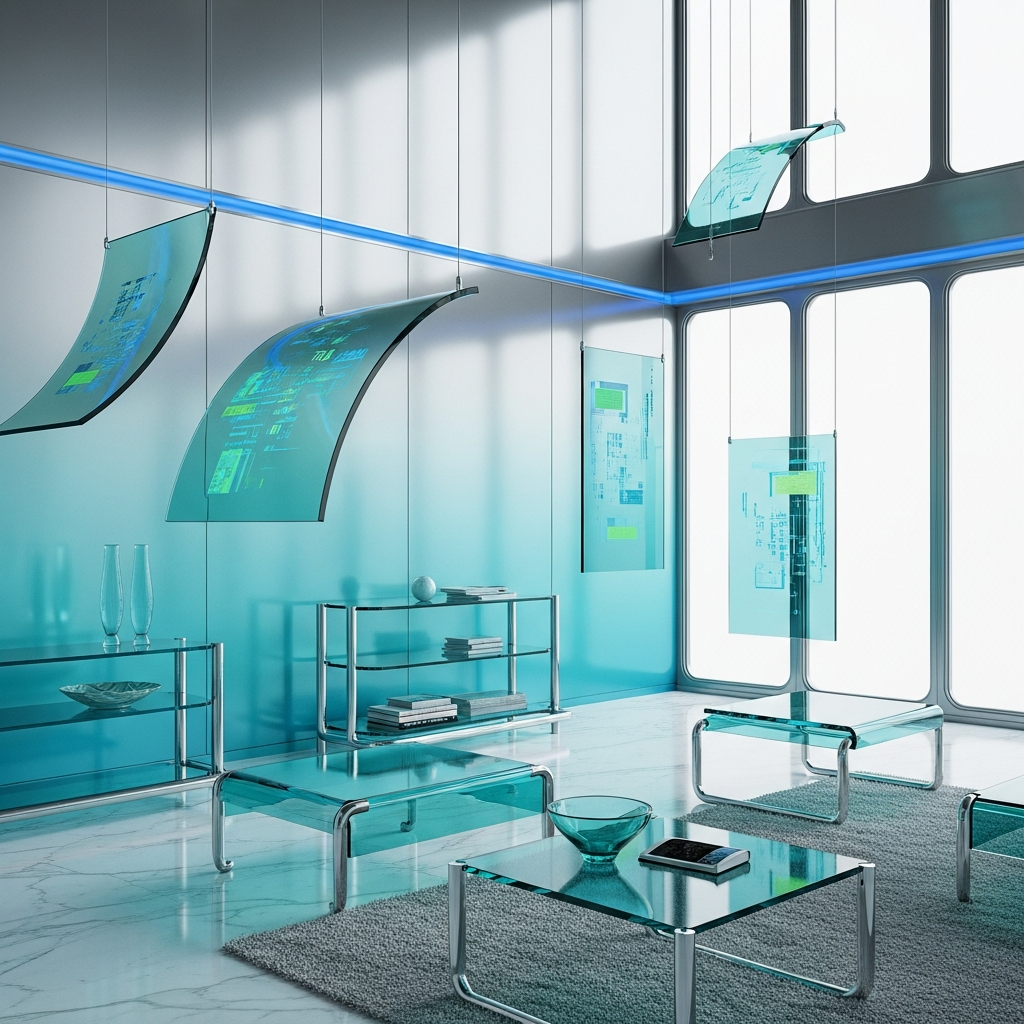

The 1960s were an era of experimentation in architecture—a time when the boundaries between art, technology, and social utopia blurred into one continuous curve. Among the most radical expressions of that decade’s optimism were inflatable pavilions: translucent, air-filled structures that seemed to defy gravity and permanence. Today, more than half a century later, these retro bubble architectures are being reimagined through the lens of sustainability, digital fabrication, and experiential design. The result is a new generation of pneumatic forms that fuse nostalgia with innovation, ephemeral beauty with environmental intelligence.

The Origins of Inflatable Architecture

Inflatable architecture emerged in the postwar years as a symbol of liberation from the rigidity of modernism. Architects like Buckminster Fuller, Archigram, and the Austrian collective Haus-Rucker-Co envisioned cities made of air—lightweight, mobile, and endlessly adaptable. Their pneumatic pavilions, often constructed from PVC or Mylar, embodied the countercultural spirit of the 1960s: anti-institutional, participatory, and playful. These structures were not just shelters but manifestos—temporary bubbles of freedom inflated against the backdrop of industrial society.

From the “Cushicle” by Archigram to the Oase No. 7 by Haus-Rucker-Co, these early experiments transformed the architectural landscape. They questioned the permanence of buildings and celebrated the idea of impermanence—a concept that resonates strongly in today’s age of climate consciousness and circular design. As cities now grapple with issues of adaptability and sustainability, the lessons of these early pneumatic pioneers are being rediscovered and reinterpreted.

Contemporary Revivals: Air as a Sustainable Medium

The resurgence of inflatable architecture in the 21st century is not mere retro-futurism. It’s a pragmatic response to contemporary challenges. Modern materials—such as ETFE (ethylene tetrafluoroethylene), recycled TPU, and bio-based polymers—have replaced the fragile plastics of the 1960s, offering greater durability, recyclability, and energy efficiency. ETFE, for instance, is the same material used in the Allianz Arena in Munich and the Eden Project in Cornwall, proving that lightweight membranes can achieve both architectural grandeur and environmental responsibility.

Today’s bubble structures are often designed with integrated photovoltaic films, passive ventilation systems, and modular anchoring that allows for rapid assembly and disassembly. These qualities make them ideal for temporary installations, disaster relief shelters, and pop-up cultural events. In a world increasingly defined by mobility and impermanence, the inflatable pavilion offers a poetic yet practical model for adaptable architecture.

The growing emphasis on biodegradable architecture has also inspired designers to experiment with air-supported forms made from compostable membranes or mycelium-infused fabrics. Such innovations align with the broader movement toward zero-waste construction and ephemeral design thinking.

Case Studies: Reimagining the Bubble

In recent years, several architects and studios have revived the spirit of 1960s pneumatic design with contemporary flair. Atelier YokYok’s “Cloud Temple” in Paris, for example, uses inflated textile modules to create a meditative, cloud-like canopy that filters light into soft gradients. The installation’s form is both sculptural and atmospheric, inviting visitors to experience architecture as a living, breathing organism.

Similarly, the Spanish studio DOSIS reinterpreted the inflatable pavilion with their “Bubble Building”—a modular educational space that can be deflated, transported, and reassembled anywhere. Its transparent skin and luminous interior evoke the utopian optimism of the 1960s while integrating solar-powered lighting and natural ventilation. The structure becomes a metaphor for adaptability, echoing the principles explored in responsive design.

Meanwhile, at Milan Design Week, the collective Plastique Fantastique presented “The Breathable Pavilion”, a translucent dome that responds to human presence through subtle air pressure changes. Visitors stepping inside experience a shift in temperature, sound, and light—a multisensory encounter that blurs the line between architecture and performance art. This immersive approach reflects a growing interest in interactive installations that engage users on emotional and physical levels.

Technology and the New Pneumatics

Advancements in computational design and digital fabrication have revolutionized how inflatable structures are conceived and realized. Architects now use parametric modeling tools to simulate airflow, pressure distribution, and structural behavior, ensuring both stability and aesthetic precision. The once unpredictable nature of air-supported forms has evolved into a finely tuned design language.

3D printing technologies are also transforming the field. Hybrid systems that combine rigid printed joints with flexible membranes allow for semi-permanent pneumatic constructions—bridging the gap between architecture and industrial design. These developments echo the ethos of parametric design, where algorithms and material intelligence converge to produce complex, organic geometries.

In addition, smart sensors embedded within the membranes can monitor internal pressure, temperature, and air quality in real time. This integration of data-driven feedback loops turns inflatable architecture into a responsive ecosystem—an idea reminiscent of the “living architecture” explored in biomimetic research. The result is a form of design that is not only visually striking but also self-regulating and energy-efficient.

From Counterculture to Climate Culture

What began as a countercultural experiment has evolved into a serious architectural discourse on sustainability and temporality. The retro bubble aesthetic—once associated with utopian escapism—now aligns with the ethics of environmental responsibility. The same qualities that made inflatables radical in the 1960s—lightness, mobility, and impermanence—are precisely what make them relevant today.

Architects are increasingly embracing the notion of “soft architecture,” where structures adapt to human and environmental needs rather than imposing rigid forms. This shift mirrors the growing interest in biophilic design and sensory-driven spaces that prioritize well-being and ecological harmony. The bubble, once a symbol of isolation, has become a metaphor for interconnection—between people, nature, and technology.

Even in urban contexts, inflatable interventions are being used to reclaim underutilized spaces. Temporary domes, air-filled corridors, and pop-up theaters are transforming rooftops, plazas, and industrial sites into dynamic cultural venues. These projects redefine public space as something fluid and participatory, challenging the traditional boundaries of architecture.

The Aesthetics of Air: A New Visual Language

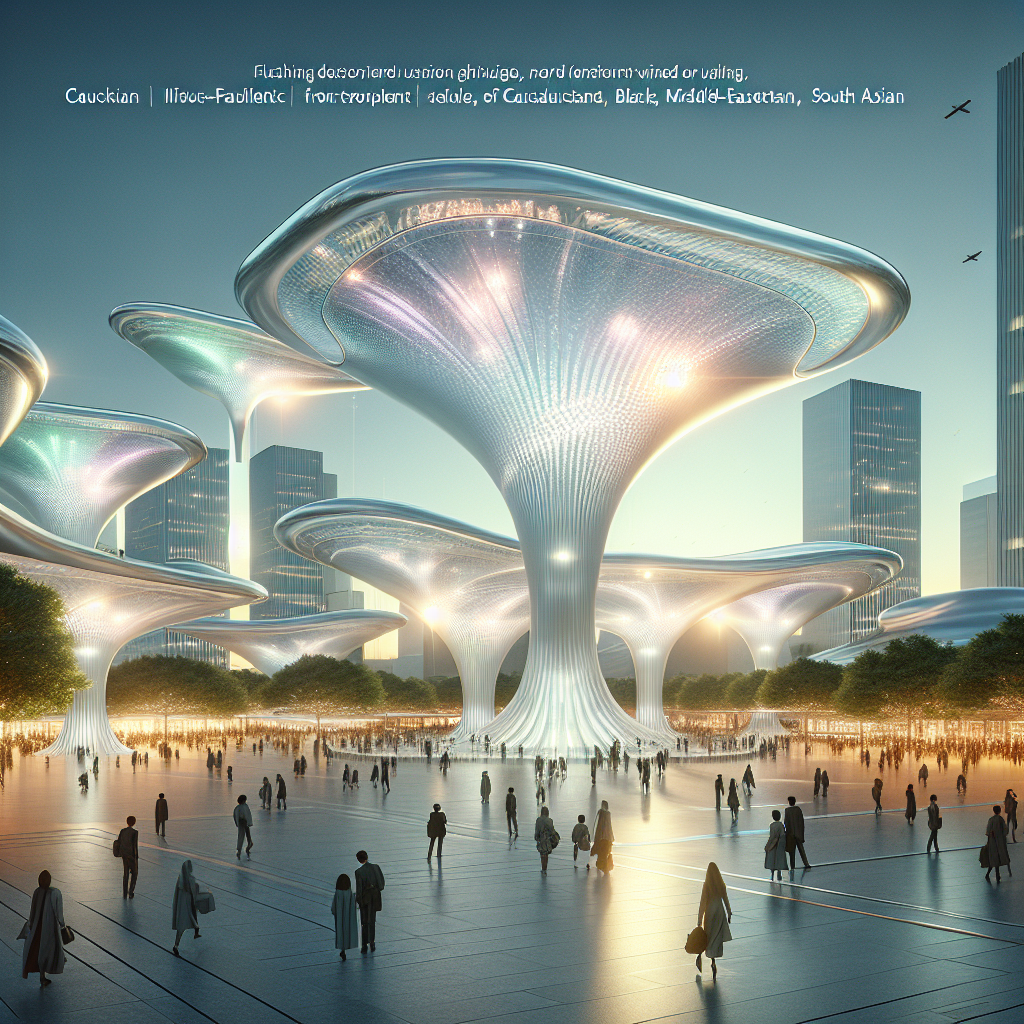

Visually, the appeal of bubble architecture lies in its ethereal translucency and soft curvature. The play of light across its surface—whether diffused through milky membranes or refracted through iridescent films—creates an atmosphere of dreamlike suspension. Interiors glow with a gentle luminescence, their boundaries dissolving into gradients of shadow and reflection. This visual softness contrasts sharply with the angularity of contemporary urban environments, offering a sense of calm and wonder.

Designers are increasingly using color, texture, and light to enhance the sensorial impact of these spaces. Some inflatables incorporate thermochromic pigments that shift hue with temperature, while others integrate LED systems that pulse in rhythm with ambient sound. The result is an architecture that feels alive—an evolving skin that responds to its surroundings and its inhabitants.

Ephemeral Futures

As the world faces mounting environmental and social challenges, the idea of architecture as a permanent monument is being reexamined. The new wave of inflatable pavilions embodies a different philosophy—one that values adaptability, circularity, and emotional resonance over material permanence. These structures remind us that architecture can be both temporary and transformative, both light and profound.

In the end, the revival of retro bubble architecture is not about nostalgia but about reimagining the future through the past. It invites architects and designers to think beyond the static and embrace the fluid—to design not just with materials, but with air, light, and imagination. In doing so, they continue the legacy of those 1960s visionaries who dared to dream of cities that breathe.

Keywords: retro bubble architecture, inflatable pavilions, pneumatic design, sustainable architecture, ephemeral structures, responsive design, biophilic design, parametric architecture