Geoengineering Architecture: Can Buildings Help Reverse Climate Change?

Geoengineering Architecture: Can Buildings Help Reverse Climate Change?

In the age of planetary urgency, architecture is no longer just about shelter, aesthetics, or even sustainability—it is about survival. As the built environment accounts for nearly 40% of global carbon emissions, architects and designers are now exploring a radical frontier: geoengineering architecture. This emerging discipline reimagines buildings not merely as passive consumers of resources but as active participants in climate repair. The question is no longer how to minimize harm, but whether architecture itself can reverse the damage already done.

The Shift from Sustainable to Regenerative Design

For decades, the architectural conversation has revolved around green architecture—designing buildings that consume less energy, produce less waste, and harmonize with nature. Yet, as the climate crisis accelerates, the industry is evolving beyond sustainability toward regeneration. Geoengineering architecture takes cues from large-scale environmental interventions such as carbon dioxide removal and solar radiation management, but translates them into the language of design and construction.

Imagine a building that doesn’t just achieve net-zero emissions but actively cleans the air, sequesters carbon, and cools its surroundings. This is the promise of regenerative architecture—a built environment that heals rather than harms. It’s a vision aligned with the ethos explored in net-zero design strategies, yet it pushes the boundaries into a new ecological paradigm.

Buildings as Atmospheric Machines

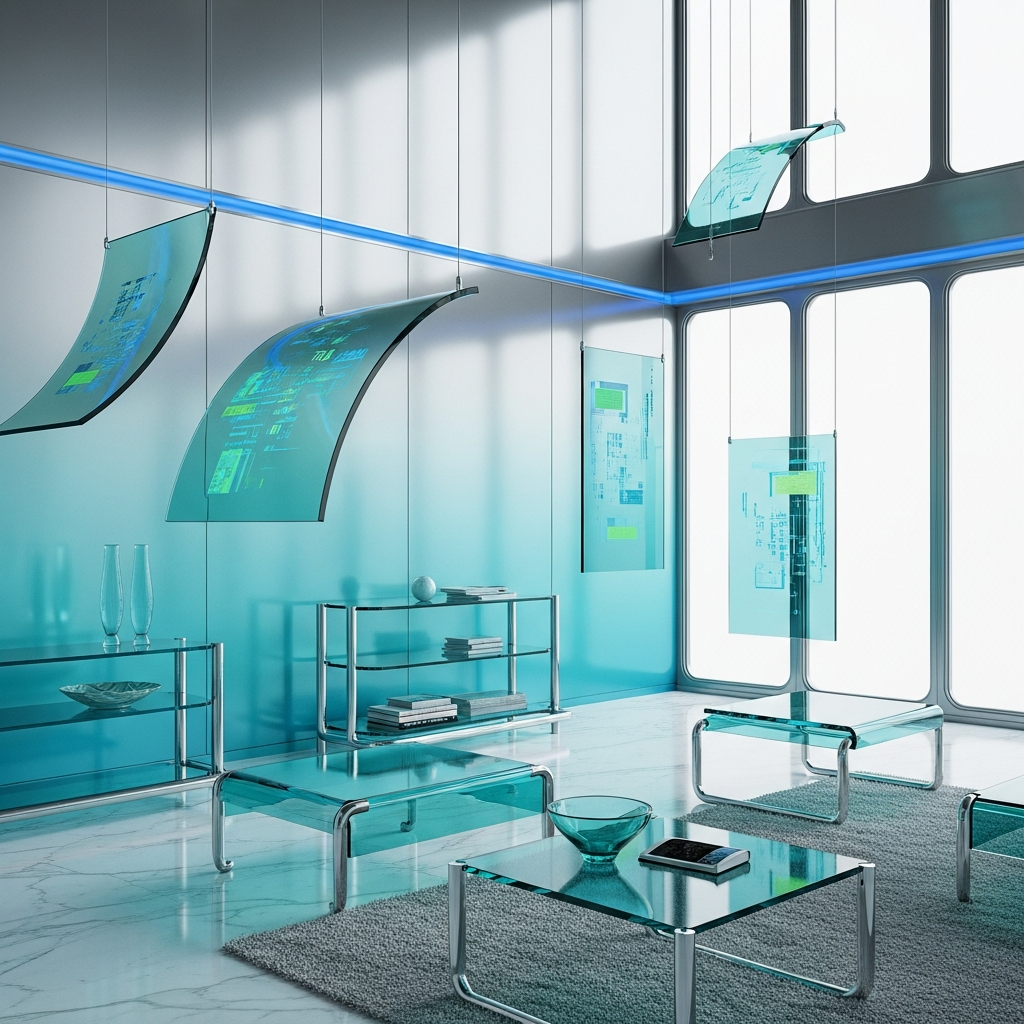

At the heart of geoengineering architecture lies the concept of the building as a climate machine. These structures go beyond energy efficiency; they are designed to interact dynamically with the atmosphere. One of the most promising approaches involves carbon-capturing materials. Concrete infused with mineralizing bacteria, for instance, can absorb CO₂ from the air, effectively turning facades into urban carbon sinks. Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have developed “living concrete” that grows and regenerates itself using cyanobacteria—an innovation that blurs the line between biology and architecture.

Another frontier is photocatalytic surfaces. Titanium dioxide coatings, when exposed to sunlight, trigger chemical reactions that break down pollutants and convert CO₂ into less harmful compounds. Buildings like the Torre de Especialidades in Mexico City already employ this technology, their shimmering white exteriors acting as vast air purifiers. These facades transform smog into harmless salts, offering a glimpse of how architecture could literally scrub the sky.

Urban Ecosystems and Atmospheric Cooling

Beyond carbon capture, geoengineering architecture also tackles the urban heat island effect—a phenomenon where cities trap heat due to dense construction and limited vegetation. Architects are increasingly turning to green roofs and vertical gardens as living infrastructures that regulate temperature, absorb CO₂, and foster biodiversity. These designs echo the principles of biophilic design, merging human well-being with planetary health.

The Bosco Verticale in Milan remains a defining example: two residential towers enveloped in over 900 trees and 20,000 plants. This vertical forest absorbs approximately 30 tons of CO₂ annually while producing oxygen and shading the city below. Similarly, Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay integrates massive “Supertrees” that function as both solar collectors and air purifiers, creating a self-sustaining urban ecosystem. These projects demonstrate that climate-positive architecture can be both poetic and performative—a choreography of ecology and engineering.

Geoengineering at the Material Scale

The materials revolution is central to this new architectural movement. Beyond the well-documented rise of mass timber construction, which sequesters carbon naturally, innovators are experimenting with materials that mimic geological processes. “Biochar concrete,” for instance, integrates carbonized organic waste into cement, locking carbon away for centuries. Similarly, algae-based bioplastics and mycelium composites offer biodegradable alternatives to petrochemical materials, transforming waste into architecture.

These materials not only reduce embodied carbon but can also be designed to absorb atmospheric carbon over time. The concept of “carbon-negative construction” is gaining traction, with companies like Prometheus Materials and Made of Air leading the charge. Their prototypes suggest a future where every wall, floor, and ceiling becomes a micro-scale carbon sink—architecture as infrastructure for planetary repair.

From Passive Design to Planetary Engineering

Geoengineering architecture represents a philosophical shift from passive design strategies to active planetary intervention. While traditional sustainable architecture focuses on minimizing impact, geoengineering architecture aspires to positive impact. It borrows from the ambition of geoengineering but grounds it in tangible, localized interventions.

For instance, architects are exploring how building envelopes can manipulate microclimates through controlled albedo (reflectivity). Highly reflective “cool roofs” and facades can reduce solar absorption, mitigating urban heat. Some experimental projects in the Middle East employ thermochromic materials that adjust their color and reflectivity based on temperature, dynamically responding to environmental conditions. These innovations recall the adaptive principles found in ancient desert architecture, reinterpreted through a high-tech lens.

Ethical and Aesthetic Dimensions

The aesthetic of geoengineering architecture is inherently futuristic yet grounded in ecological ethics. Its visual language often blends organic forms with high-performance surfaces—think of shimmering bioreactors embedded in glass facades or moss-covered atria filtering indoor air. This new aesthetic challenges the modernist notion of purity and control, embracing instead a living, evolving materiality.

Yet, the ethical implications are complex. As with large-scale geoengineering, questions arise about unintended consequences and ecological balance. Could buildings designed to manipulate the atmosphere disrupt local weather patterns? Might the reliance on high-tech materials increase resource extraction elsewhere? These are not merely technical issues but moral ones, demanding a new kind of architectural responsibility—one that considers planetary systems as design clients.

Case Studies: Prototypes of a Climate-Repairing Future

Across the globe, experimental projects are testing the boundaries of what geoengineering architecture can achieve. In Hamburg, the BIQ House uses algae-filled glass panels to generate biofuel while shading interiors. The panels absorb CO₂ and produce biomass, effectively turning the building into a vertical bioreactor. In Iceland, the CarbFix project integrates architecture with geological carbon storage, where captured CO₂ is mineralized underground through basaltic rock formations.

Meanwhile, speculative designs such as the “Urban Sequoia” concept by SOM envision skyscrapers that act as carbon sponges, absorbing more CO₂ than they emit. These towers would use bio-based materials, algae systems, and direct air capture technology to create a new typology of carbon-negative urbanism. The ambition is clear: to transform cities from sources of pollution into engines of planetary restoration.

Architecture as a Tool for Climate Repair

The idea that architecture could reverse climate change might once have seemed utopian. Yet, as technological, biological, and material innovations converge, this vision is rapidly entering the realm of feasibility. The next generation of architects will not only design for human comfort but for atmospheric equilibrium. Buildings will become active agents in Earth’s climate system—absorbing carbon, generating clean energy, and nurturing biodiversity.

Geoengineering architecture is not a replacement for global emissions reduction, but it offers a crucial complement. It transforms the built environment into a distributed network of climate interventions, where every structure contributes to planetary healing. In this sense, architecture becomes a form of activism—an art of repair that merges design intelligence with ecological empathy.

As we stand at the intersection of crisis and creativity, the question is no longer whether architecture can help reverse climate change, but how boldly we are willing to reimagine its role. The buildings of tomorrow may not just reflect our values—they may regenerate the very world that sustains them.

Keywords: geoengineering architecture, regenerative design, carbon-negative buildings, sustainable architecture, climate-positive design, carbon capture materials, urban heat island mitigation, biophilic architecture