Designing for Mental Health: How Architecture Shapes Our Emotional Landscape

Designing for Mental Health: How Architecture Shapes Our Emotional Landscape

In an era where urban density, digital overload, and environmental anxiety define much of daily life, the role of architecture in supporting mental health has never been more critical. Beyond aesthetics and function, the built environment profoundly influences how we feel, think, and connect. Architects and designers are increasingly recognizing that spaces can act as both mirrors and mediators of our emotional states—offering calm, stimulation, or even healing through thoughtful design. This paradigm shift, often described as therapeutic architecture or neuroarchitecture, reframes buildings not as static objects but as dynamic participants in human well-being.

The Emotional Blueprint: How Space Affects the Mind

Our brains are hardwired to respond to spatial cues. Studies in environmental psychology reveal that light, proportion, materiality, and spatial flow can alter cortisol levels, influence mood, and even affect cognitive performance. For instance, natural light exposure has been linked to improved circadian rhythms and reduced symptoms of depression, while confined, poorly ventilated spaces can heighten stress and fatigue.

Architectural theorists like Juhani Pallasmaa have long argued that architecture is not merely visual—it is multisensory. The scent of timber, the texture of stone, or the acoustic softness of fabric panels all contribute to an embodied experience of space. This understanding is now shaping design strategies in hospitals, schools, and workplaces, where the goal is not only to house activity but to enhance mental resilience.

Biophilic Design: Nature as a Healer

Among the most influential movements in this field is biophilic design, which integrates natural elements into architecture to foster psychological restoration. The principle is simple yet profound: humans thrive when connected to nature. Whether through living walls, daylight optimization, or organic materials, biophilic environments have been shown to lower blood pressure, improve concentration, and elevate mood.

Consider the Maggie’s Centres across the UK—cancer care facilities designed by leading architects such as Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid. Each center employs biophilic principles through garden courtyards, tactile materials, and open, light-filled interiors. These spaces eschew clinical sterility in favor of warmth and dignity, embodying the belief that architecture can be a form of emotional therapy.

In urban contexts, the same ethos is being applied to residential and public projects. The rise of green roofs and vertical gardens in dense cities like Singapore and Milan exemplifies how design can reconnect inhabitants with living ecosystems, even amid concrete jungles.

Light, Color, and Sound: The Sensory Dimensions of Well-Being

Lighting design, often overlooked, is emerging as a cornerstone of mental health architecture. Dynamic lighting systems that mimic the natural progression of daylight can regulate melatonin production and support emotional balance. In Scandinavian countries, where winter darkness can trigger seasonal affective disorder, architects are experimenting with full-spectrum LED systems and reflective surfaces to simulate sunlight’s psychological effects.

Color psychology also plays a subtle yet powerful role. Muted tones—sage greens, soft blues, and warm neutrals—are increasingly favored in wellness-oriented interiors for their calming properties. The art of chromatic harmony has evolved from mere decoration into a science of emotional modulation, where each hue contributes to the occupant’s mental equilibrium.

Acoustics, too, are integral. The growing emphasis on acoustic comfort recognizes that soundscapes influence concentration and relaxation. Materials like cork, felt, and perforated wood panels are being used to absorb noise and create auditory sanctuaries in open-plan offices and communal housing.

Designing for Solitude and Connection

Modern architecture often celebrates openness—vast glass façades, continuous floor plans, and shared amenities. Yet, as mental health research underscores, humans also crave privacy and introspection. The emerging trend of designing for solitude responds to this need by integrating quiet nooks, reading alcoves, and meditation pods within larger communal environments. These micro-sanctuaries allow individuals to retreat without disconnecting entirely from social life.

Conversely, communal design can foster belonging and reduce loneliness. Projects like co-housing developments and community gardens demonstrate how spatial design can encourage social interaction, empathy, and shared purpose. The balance between solitude and connection—between retreat and engagement—is becoming a defining metric of emotionally intelligent architecture.

Case Study: The Healing Library

In Helsinki, the Oodi Central Library redefines what a civic building can be. Beyond books, it offers workshops, play areas, and quiet zones—all under a vast timber canopy that filters daylight into a warm, golden glow. The design prioritizes mental comfort: soft seating, tactile materials, and acoustically balanced zones create a sense of serenity amid urban bustle. It’s a living example of how public architecture can act as a collective “third space” for mental restoration.

Similarly, projects like the Healing Library concept merge architecture with therapy, embedding wellness rooms within cultural institutions. Such initiatives illustrate a growing awareness that mental health support need not be confined to hospitals—it can be seamlessly woven into everyday civic life.

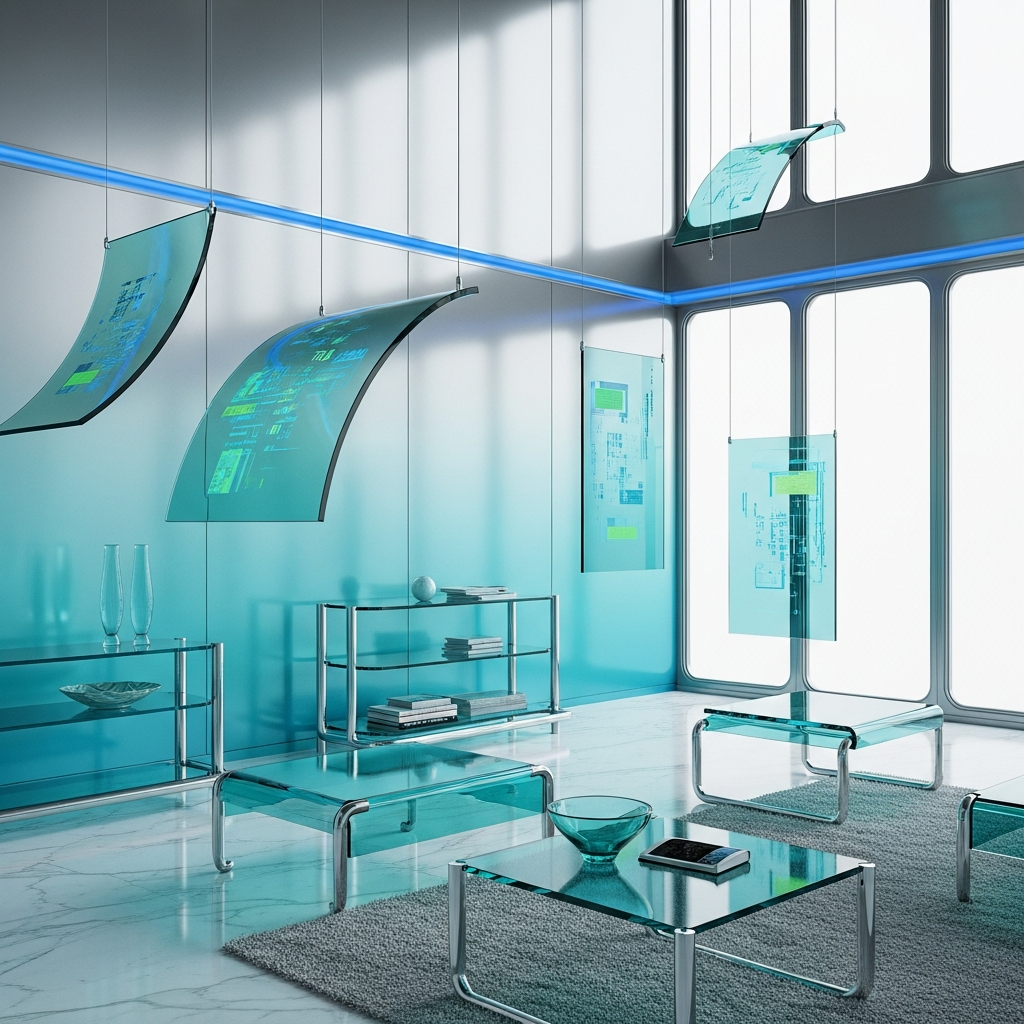

Technology and the Future of Emotional Design

As smart technologies become embedded in architecture, designers are exploring how responsive systems can adapt to emotional states. AI in architecture now enables spaces that adjust lighting, temperature, and sound based on biometric feedback. These “empathetic environments” could soon become standard in workplaces and homes, offering personalized comfort and stress reduction.

Yet, the integration of technology raises philosophical questions. Can emotional well-being be automated? Or does true healing still depend on the tactile, the organic, the imperfect? The emerging dialogue between digital precision and human vulnerability is shaping a new frontier—one where architecture becomes both data-driven and deeply humane.

From Design to Advocacy: A New Professional Ethos

Designing for mental health is not a stylistic trend—it’s a moral imperative. As the World Health Organization reports that one in four people will experience mental health challenges in their lifetime, architects hold unprecedented power to influence collective well-being. This responsibility extends beyond hospitals or wellness centers to every typology—from schools and offices to transport hubs and housing.

Progressive firms are already embedding mental health criteria into design briefs, using post-occupancy evaluations to measure emotional outcomes. The conversation is shifting from “How does it look?” to “How does it make us feel?”—a subtle but seismic change in the discipline’s priorities.

The Architecture of Empathy

Ultimately, designing for mental health is about empathy translated into form. It’s about recognizing that architecture is not neutral—it shapes our rhythms, relationships, and resilience. A corridor bathed in soft light, a courtyard that invites pause, a window framing a tree—these are not aesthetic luxuries but essential gestures of care.

As the global design community continues to explore sustainability, inclusivity, and innovation, the emotional dimension of architecture offers a profound new lens. Spaces that heal are not only beautiful—they are humane. And in a world increasingly defined by noise and speed, the quiet architecture of empathy may be the most radical design movement of all.

Keywords: mental health architecture, therapeutic design, biophilic design, emotional well-being, neuroarchitecture, sensory design, architectural psychology

Related Reading: Explore how spatial psychology informs emotional design, or discover the role of responsive architecture in creating adaptive environments for well-being.