Velvet architecture plush: façade treatments for tactile city experiences

Velvet Architecture Plush: Façade Treatments for Tactile City Experiences

In an era where urban architecture increasingly engages the senses beyond sight, a new material language is emerging—one that invites touch, texture, and intimacy. The concept of “velvet architecture plush” redefines façades not as static skins but as tactile mediators between the built environment and its inhabitants. This movement, rooted in material innovation and sensory design, is reshaping how cities feel—literally. Architects and designers are now crafting façades that whisper rather than shout, offering surfaces that absorb light, soften acoustics, and invite human connection through texture.

The Rise of Tactile Urbanism

For decades, the modern city has been dominated by glass, steel, and concrete—materials that reflect progress but often repel touch. As urban life accelerates, designers are seeking ways to slow it down, to create moments of sensory grounding. This shift parallels the rise of sensory design in interiors, where tactility is increasingly valued as a form of emotional comfort. Now, this philosophy is migrating outdoors, transforming façades into velvet-like surfaces that blur the boundary between architecture and art.

According to a 2025 report by the World Green Building Council, multisensory design principles are becoming central to sustainable urban development. The tactile façade—whether through fabric-inspired cladding, bio-based composites, or textured ceramics—serves not only aesthetic purposes but also contributes to thermal regulation, sound absorption, and human well-being.

Material Innovation: From Soft Illusion to Structural Reality

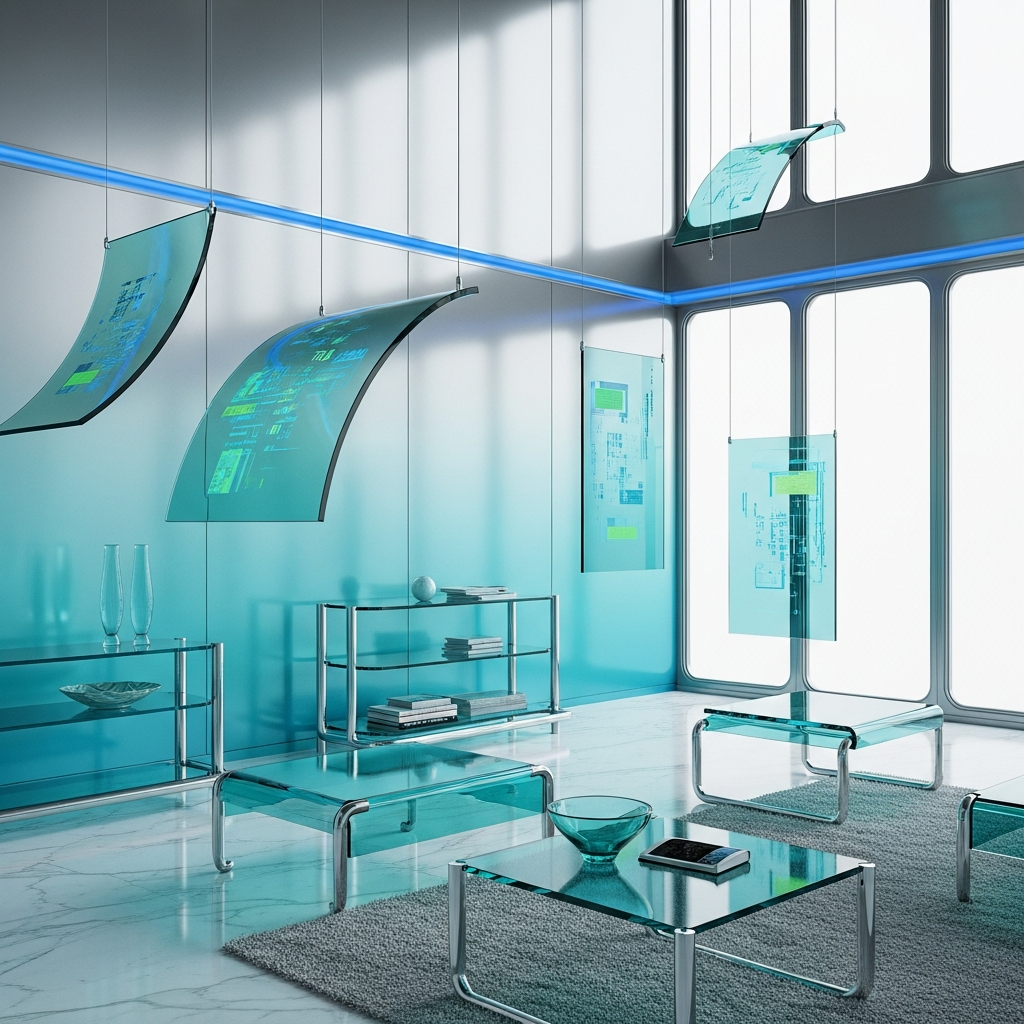

The term “velvet architecture” does not imply literal softness but rather the illusion of plushness achieved through material depth, color gradation, and surface modulation. Architects are experimenting with micro-topographies—ridges, folds, and undulations that mimic the way velvet interacts with light. These façades shift in tone and texture as daylight moves, creating dynamic, almost haptic visual experiences.

One notable example is Herzog & de Meuron’s Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, whose glass panels are embossed with subtle convexities that scatter light like fabric fibers. Similarly, Japanese architect Junya Ishigami’s projects often employ matte coatings and porous materials that evoke the softness of textiles while maintaining structural integrity. The result is a façade that seems to breathe—absorbing light, diffusing sound, and inviting the gaze to linger.

Emerging technologies such as sand-printing fabrication and 3D ceramic extrusion are expanding the possibilities for tactile façades. These techniques allow for intricate surface detailing that was once impossible through traditional casting or paneling methods. The result is a new generation of buildings that feel hand-crafted, even when digitally produced.

Urban Velvet: Softness as a Counterpoint to Density

In dense metropolitan contexts, softness becomes a form of resistance. The plush façade offers psychological relief from the city’s visual and acoustic overload. It introduces a sense of urban tactility—a design strategy that prioritizes sensory diversity over uniformity. In Paris, for instance, experimental façades incorporating suede-like microfibers have been tested for their ability to trap particulate matter while offering a visually soothing texture. In Copenhagen, moss-covered acoustic panels are redefining street-level experiences, merging biophilic and tactile design in a single gesture.

This convergence aligns with the principles of biophilic design, which emphasizes the restorative power of natural textures. Velvet-inspired façades often employ organic materials—compressed hemp, recycled wool composites, or cellulose-based coatings—that age gracefully, acquiring patina rather than decay. These materials echo the wabi-sabi philosophy of beauty in imperfection, transforming the city into a living, evolving fabric.

Case Studies: From Conceptual to Constructed

Several projects around the world are already embodying the “velvet architecture plush” ethos. In Milan, Studiopepe’s recent pavilion for Design Week featured a façade wrapped in thermochromic textiles that changed hue with temperature shifts—an architectural garment responding to its environment. In Los Angeles, Morphosis Architects have explored micro-fibered concrete panels that diffuse light in a velvety gradient, softening the building’s monumental scale.

Meanwhile, in Seoul, the “Soft Brutalism” movement has gained traction, blending concrete’s raw power with tactile overlays of felt, cork, and recycled denim. This aesthetic dialogue between hardness and softness recalls the experimental spirit of Soft Brutalism, where material contrast becomes a metaphor for urban empathy—an architecture that both protects and caresses.

Technology Meets Texture

Digital fabrication tools are instrumental in achieving these new tactile effects. Parametric modeling allows designers to simulate how light interacts with micro-textures, predicting the emotional and sensory response of users. In parallel, responsive materials—such as kinetic façades—are being integrated with soft-surface technologies, enabling façades that shift texture or sheen in response to environmental stimuli.

Some experimental prototypes use electrostatic fibers that stand upright when charged, creating a literal “velvet” surface that can change density or directionality. These responsive façades are not only aesthetic marvels but also energy-efficient systems capable of modulating heat gain and airflow. As smart materials evolve, the line between architecture and fashion continues to blur—buildings that dress and undress themselves according to the weather or mood of the city.

The Psychology of Touch in Urban Design

Beyond the technical, the appeal of velvet architecture lies in its emotional resonance. Touch is the first sense we develop and the last we lose; it anchors us in the physical world. In a digital age dominated by screens and abstraction, tactile architecture restores a sense of presence. The plush façade becomes a civic gesture—a reminder that cities are not just visual compositions but lived, felt environments.

Studies in environmental psychology suggest that textured surfaces can reduce stress and enhance feelings of safety and belonging. A 2024 survey by the European Institute of Urban Studies found that pedestrians were 37% more likely to linger near buildings with tactile façades than near smooth, reflective ones. The implication is profound: texture influences behavior, social interaction, and even urban economics.

Future Directions: Toward a Haptic City

As sustainability converges with sensory design, the next frontier of urban architecture may well be haptic urbanism—cities designed to be touched, not just seen. Architects are already envisioning façades that integrate sound-dampening velvet composites, thermally adaptive fibers, and bioluminescent mosses that glow softly at night. These innovations echo the broader trend toward biodegradable architecture, where material tactility and ecological responsibility coexist.

In this context, the velvet façade becomes more than an aesthetic statement—it becomes a manifesto for urban gentleness. It signals a departure from the sterile, glass-clad modernism of the past toward a more empathetic architecture, one that acknowledges the human need for softness amid the city’s relentless pace.

A New Urban Sensibility

To walk through a city draped in velvet architecture is to experience a choreography of light, shadow, and touch. Buildings no longer stand aloof; they engage, comfort, and converse. This tactile revolution is not about nostalgia for craft but about rehumanizing the metropolis through material empathy. It invites architects to design not only for the eye but for the hand, the skin, and the psyche.

As the boundaries between digital and physical dissolve, and as sustainability demands more than efficiency, the plush façade stands as a symbol of a new urban sensibility—one that values intimacy over spectacle, and texture over transparency. The velvet city is not a dreamscape; it is the next logical step in the evolution of architecture that feels alive.

In the words of one Milan-based architect, “We have built cities to be seen from afar. Now, we must build them to be felt up close.” The velvet revolution has begun—quietly, softly, and with extraordinary depth.

Keywords: velvet architecture, tactile façades, sensory design, haptic urbanism, soft brutalism, material innovation, biophilic architecture, sustainable design trends

Published on: 01/15