Sinuous corridors wave-like: passages dissolving rectilinear design norms

Sinuous Corridors Wave-Like: Passages Dissolving Rectilinear Design Norms

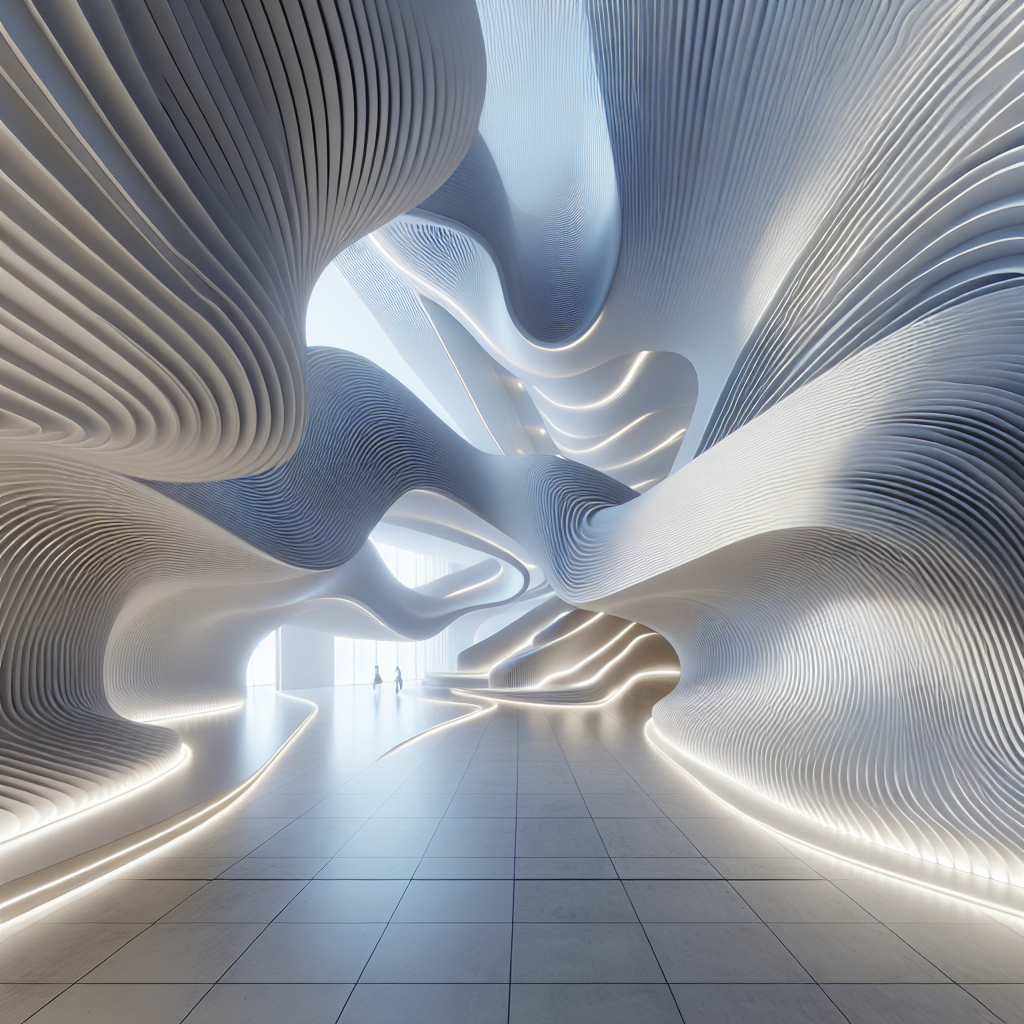

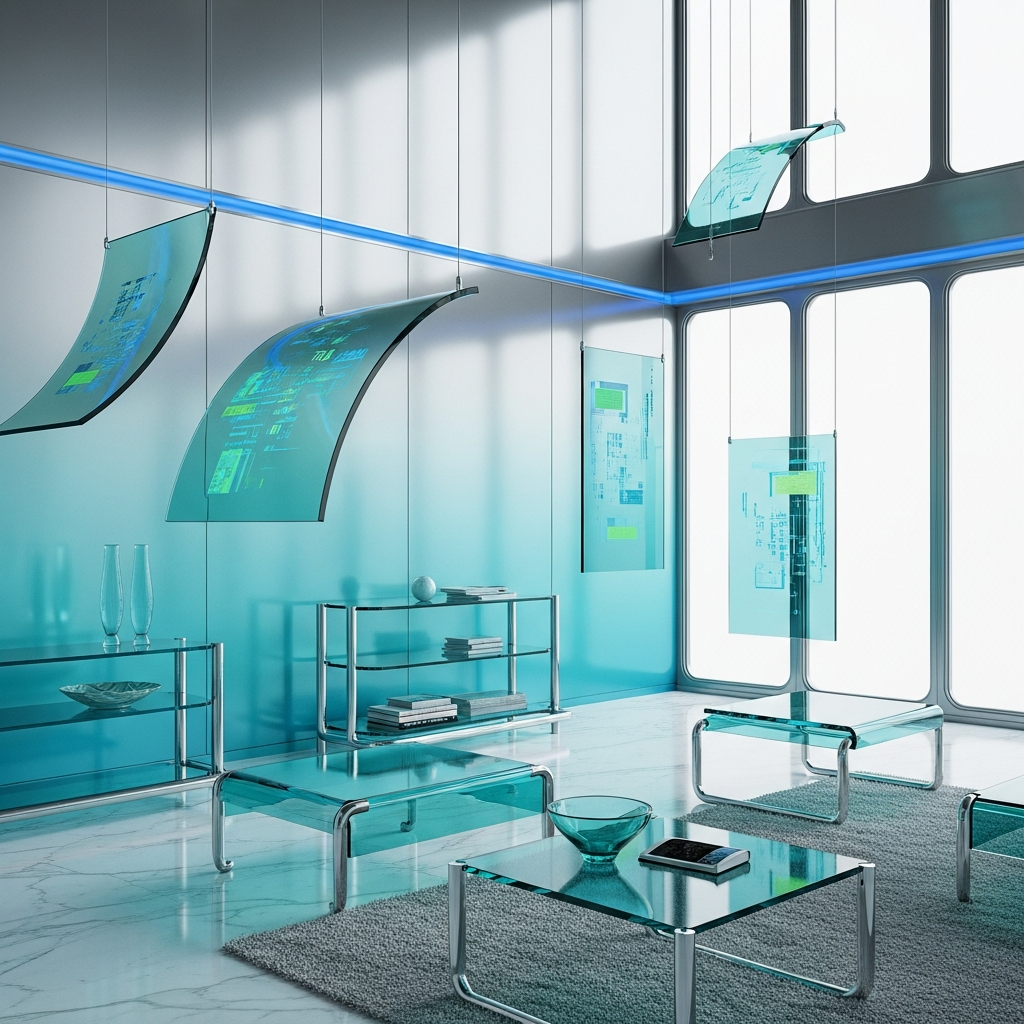

In the canon of architectural history, the corridor has long been a space of transition—functional, linear, and often overlooked. Yet in the past decade, a quiet revolution has begun to ripple through the world’s most forward-thinking studios: the sinuous corridor. These wave-like passages, bending and flowing with organic grace, are challenging the orthodoxy of rectilinear design. They invite movement not as a necessity, but as an experience—transforming circulation into choreography.

The End of the Straight Line

For centuries, the straight corridor symbolized efficiency and control. From the monastic cloisters of medieval Europe to the modernist grids of Le Corbusier, linearity represented order and rationality. Yet as digital design tools and parametric modeling matured, architects began to explore curvature not as ornament but as structure. The corridor, once a utilitarian artery, has become a site of experimentation.

Today’s curvilinear architecture is driven by both aesthetic and psychological imperatives. Studies in environmental psychology, such as those cited by the Journal of Environmental Psychology, reveal that curved spaces evoke calmness and comfort, while sharp angles can induce tension. This shift aligns with a broader movement toward biophilic design—an ethos that privileges natural forms and sensory harmony over rigid geometry.

Organic Flow: From Algorithm to Atmosphere

The emergence of wave-like corridors owes much to computational design. Software such as Rhino and Grasshopper allows architects to generate complex topologies that once defied manual drafting. These digital tools translate mathematical curves into tangible forms—corridors that undulate like dunes, ripple like water, or spiral like seashells.

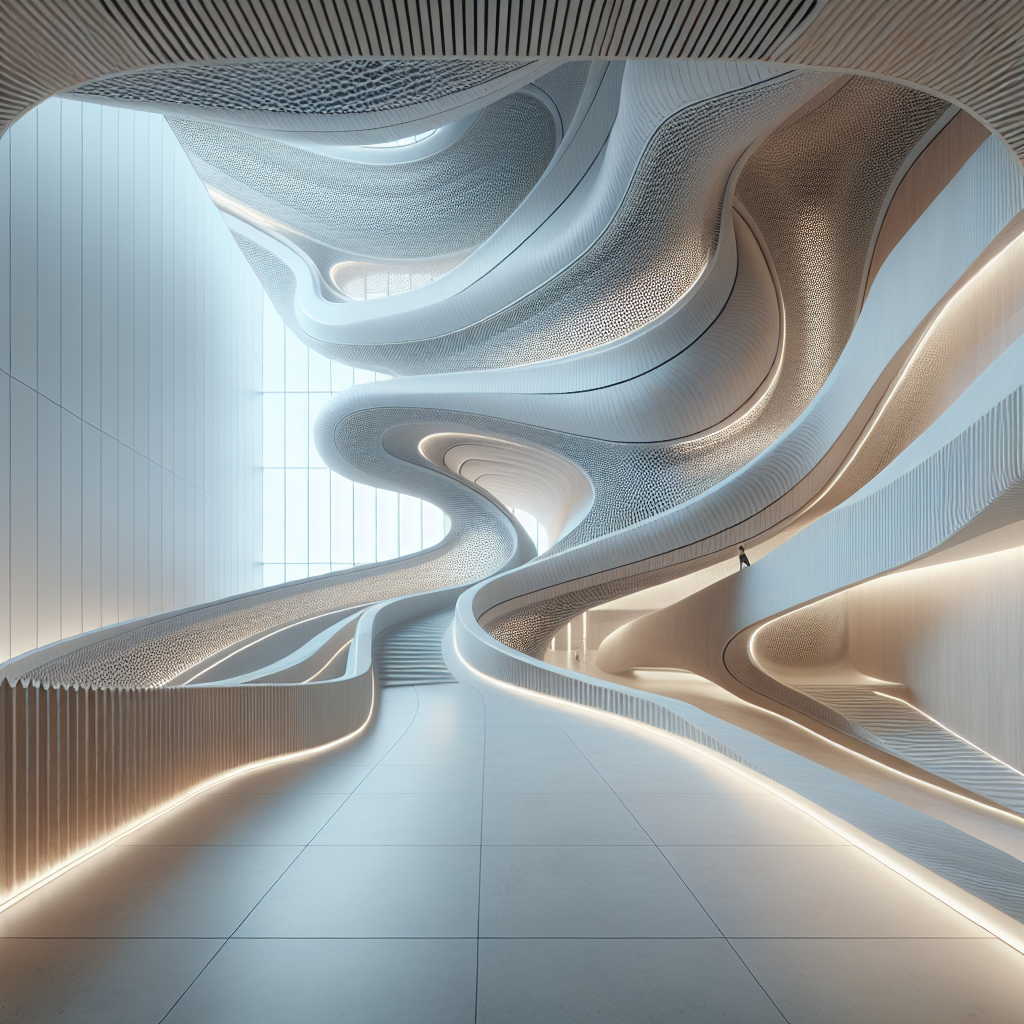

Consider the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku by Zaha Hadid Architects, where corridors merge seamlessly into walls and ceilings, dissolving boundaries in a continuous white sweep. The result is a spatial experience that feels less like walking through a building and more like gliding through a sculptural landscape. Similarly, MAD Architects’ Harbin Opera House in China envelops visitors in a fluid interior, its passageways shaped by the flow of wind and snow across the northern plains.

These designs are not merely aesthetic indulgences. They embody a new philosophy of architectural movement—one that sees circulation as narrative. Each curve, each bend, is a gesture of invitation, guiding the body through space in a rhythm that feels intuitive and human.

Material Fluidity: Crafting the Curve

The construction of sinuous corridors demands a rethinking of materials and methods. Traditional masonry and steel framing resist curvature; thus, architects turn to more pliable systems—bent laminated timber, 3D-printed concrete, and flexible composites. In this sense, the rise of the curved corridor parallels the rise of engineered timber and other adaptive materials that can be shaped into continuous, organic geometries.

Lighting, too, plays a crucial role. LED ribbons trace the contours of ceilings, emphasizing motion and depth. Diffused light washes over convex surfaces, creating gradients that mimic the natural play of sunlight on water. The corridor becomes a living organism—responsive, dynamic, and emotionally resonant.

The biomimetic approach to design—drawing inspiration from natural systems—has further accelerated this trend. Architects now use algorithms that simulate the growth of coral or the branching of rivers to generate corridor layouts that feel instinctively right. These patterns, though computationally complex, resonate with the human body’s innate preference for flow and rhythm.

Spatial Psychology and the Human Experience

The emotional impact of curvature cannot be overstated. Neuroscientific research from the University of Toronto suggests that humans are predisposed to prefer curved environments, associating them with safety and softness. This insight has profound implications for interior architecture, particularly in spaces designed for wellness, education, or healthcare.

In hospitals, for instance, curved corridors can reduce anxiety and improve wayfinding by eliminating harsh corners and dead ends. In museums, they slow the visitor’s pace, encouraging contemplation. The labyrinthine museum typology—once a metaphor for confusion—has been reimagined as a tool for engagement, where winding paths create moments of surprise and discovery.

In residential and hospitality design, wave-like passages evoke intimacy and sensuality. The gentle arc of a hallway can lead guests toward light, sound, or scent, crafting a multisensory journey. As experiential design becomes a defining feature of luxury interiors, the corridor is no longer a neutral void but a stage for emotion.

Case Studies: The Curved Corridor in Practice

One striking example is the Amanyangyun Resort near Shanghai, designed by Kerry Hill Architects. Here, corridors meander between ancient camphor trees, their glass walls reflecting the forest beyond. The architecture blurs the line between built and natural, creating a meditative rhythm of movement.

In contrast, the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris by Frank Gehry employs sweeping internal walkways that mimic the sails of its glass exterior. Visitors drift through layers of transparency and reflection, their path orchestrated like a musical composition. Gehry’s corridors are not conduits—they are experiences in themselves.

Meanwhile, in the corporate realm, offices are adopting curved circulation to foster creativity and collaboration. Google’s Bay View Campus, designed by BIG and Heatherwick Studio, features serpentine corridors that encourage spontaneous encounters. The design echoes the organic networks of the brain itself—a spatial metaphor for innovation.

Beyond Form: Sustainability and Performance

The fluid corridor is not only a visual statement but also a sustainable strategy. Curved layouts can optimize airflow, reduce acoustic reverberation, and enhance natural light distribution. By minimizing right angles, they prevent stagnant air pockets and promote passive ventilation—principles that echo ancient desert architecture, as explored in vernacular design traditions.

Moreover, digital fabrication allows for material efficiency. CNC milling and robotic extrusion produce curved panels with minimal waste, aligning with the ethos of circular design. The corridor thus becomes a microcosm of sustainable innovation—where form, function, and ethics converge.

The Future of Circulation: From Corridor to Continuum

As architecture enters an era defined by fluidity—spatial, digital, and ecological—the corridor is evolving from a transitional zone into a connective tissue. In future urban environments, we may see entire buildings conceived as continuous loops, their circulation paths integrated with energy systems, light channels, and biophilic elements.

This shift reflects a broader cultural transformation. The straight line, once a symbol of progress, now feels static in a world that values adaptability and sensory engagement. The wave, by contrast, embodies resilience and renewal. It mirrors the rhythms of nature, the flow of data, and the pulse of human life.

The sinuous corridor, then, is more than a design trend—it is a manifesto for movement. It dissolves the rigid hierarchies of modernism and replaces them with fluid continuity. It transforms architecture from a static composition into a living, breathing experience.

In the words of one contemporary architect, “Curves remind us that architecture is not just about space—it’s about time.” Each bend marks a moment, each wave a transition. Together, they compose a new spatial language—one that speaks not in lines, but in rhythms.